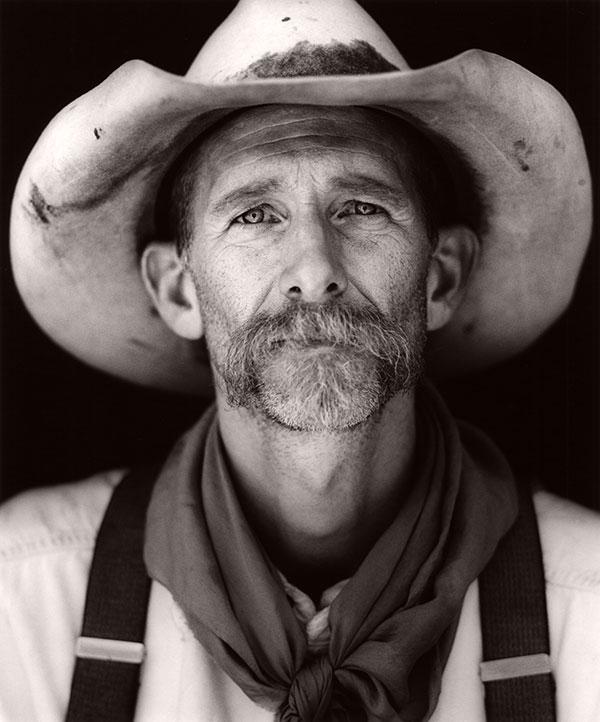

True Grit: How Michael Crouser Captures Cowboys in Colorado with Black-and-White Film

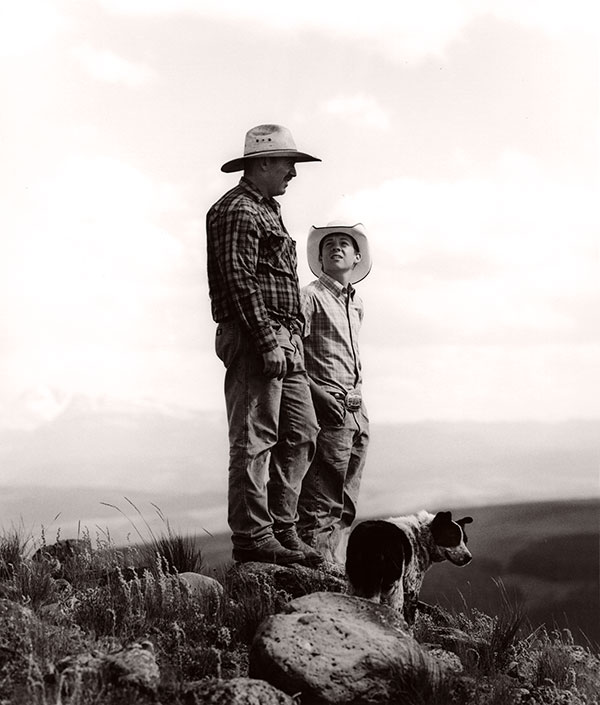

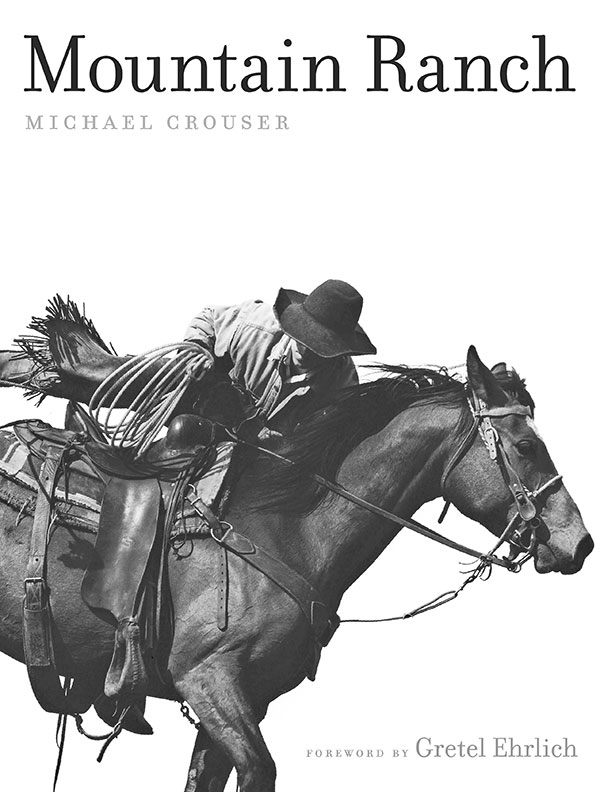

In 2006, Michael Crouser took the first photograph in his mountain ranch project. Ten years later he took the last image to complete Mountain Ranch, the book that grew from the project. He calls the book “an exploration of the disappearing world of cattle ranching in the mountains of Colorado,” but it’s more than that: it’s a story of the ties and traditions of families, and a story of an America that was, struggling to still be.

His images, made with film cameras, chronicle the yearlong cycle of the ranchers’ lives, during which he avoided “evidence of modernity.” You’ll see no sunglasses, tennis shoes, or baseball hats; none of the things, he says, “that would yank the viewer out of the story.”

Crouser, who lived in New York at the time he started the project, headed to northwestern Colorado at the suggestion of a friend who lived near the ranchers. Introductions were made, and though at first they wondered what a New Yorker was doing there, he entered the lives of nine different ranching families. “Eventually I became quite good friends with them,” he says, “as I watched their families grow and documented what I think is an important part of American culture.”

Season to Season

He set no time limit on the project. The goal was to get it right.

“If I saw a certain aspect of their lives I didn’t feel I covered well enough, I’d think, Well, I’ll go back next year at this time. At one point I was way up on a rise, watching some of the ranchers on a cattle drive. It was beautiful, but when I got home I found my camera had malfunctioned. They weren’t going to do that drive again for another year, so I knew that in a year I’d be sitting on that mountain again, taking that picture again. And that’s what I did.”

He learned the rhythms of their life and work—“they don’t work on a schedule, they work seasonally”—and he learned to adapt. “At first I was getting a lot of pictures of their backs, so I learned to be where they were going. But sometimes they’d have to tell me to get out of the road—cows don’t want to go where there’s some mysterious thing standing in their way, waiting to take pictures.”

He rarely asked them to repeat something he’d missed. “And when I did, they’d just laugh. On the other hand, I opened a lot of gates. Sitting in the front seat of their trucks, offering to get out and open them—that’s a big thing.”

So was providing prints. “I did that throughout the project. They’re all hand-made, so it takes time, but I always set aside a box of prints for the people I visited. I wanted to do it, and I also knew it helped to have a good relationship with the people I was working with.”

Most of the ranchers didn’t notice him all that much. “They’re very focused on what they’re doing—and my methods made it okay for me to be there. I didn’t ask them for anything. I didn’t need them to do anything differently. It was an observational project; I was present but inconspicuous. I didn’t talk a lot or move a lot. Some of the ranchers were more involved and interested in what I was doing, and said things like, ‘Do you want to get up on that barn? Here’s a ladder.’”

Photo Methods

Michael Crouser shoots with digital cameras for his commercial work; for personal projects, it’s film.

He shot the Mountain Ranch photos with either a Pentax 67 or a Nikon F4. His film was Kodak Tri-X. He used two lenses: an SMC 200mm f/4 for the Pentax, an AF-S Nikkor 300mm f/2.8D for the Nikon—until it bounced out of his four-wheeler, crashed to the road and was replaced by an AF-S 300mm f/4D. It turned out the replacement was “much more usable—I didn’t need anything lower than f/4 and the thing weighed about half as much as the broken lens.”

His tripod was a Gitzo Traveler, and he used two light meters at different times on the project, a Minolta Flash Meter IV and a Sekonic Flash Master L-358.

“I could use the Pentax for so many things—portraits, landscapes, even action—it does have a shutter speed of 1/1000 second—if I got close enough. That became a challenge: about halfway through I started seeing that my pictures weren’t as interesting to me as I wanted them to be, so I started getting a lot closer with the Pentax to subjects in motion. If I couldn’t get close enough, I’d use the Nikon with the 300mm lens.”

He would always try to shoot at 1/500 second at f/11 or f/8, or 1/1000 second at f/8 or f/5.6. “I wanted to narrow the range of what I brought into the darkroom—either this f/stop or that one. If you’re paying attention to your exposures and your processing, you should be getting consistent negatives to work with.”

He shot his 400-rated film at 320, “overexposing just a hair.” If he had to go up a stop he’d rate his light meter at 800 and figure out the processing—“I have a chart”—to compensate for the push. “I don’t think I ever pushed it past 800, and I had to mark the roll I shot at the 800 meter setting. Have Sharpie, will travel.”

That’s the how of it. The why—why photograph in black and white, on film—comes down to nothing more complicated than what feels right to him. The means fit the subject, and for the traditional elements in lives lived according to tradition he created images that could have been taken today or unknown yesterdays ago. “I consider myself a film person and a black-and-white person, traditional and basic,” Crouser says. “For these personal projects, I don’t know what comes first—my picking a subject or picking a medium.”

When he got back from every trip to Colorado he couldn’t wait to see the results of the shoot. “It wasn’t a chore—I’d get off the plane and the same day get into the darkroom and process film. What I first loved about photography was the darkroom, and I still do.”

You can find examples of Michael Crouser’s photography at michaelcrouser.com, along with information about workshops and his books, including Mountain Ranch, just published by the University of Texas Press.

- Log in or register to post comments