The Sandro Style: How a Portrait Master’s Personal Touch Creates Compelling Images

All Photos © Sandro

What we look at when we look at a Sandro portrait is an image that is as much about Sandro as it is about his subject. About that he is frank and fearless.

“My portraits come from my heart and from how I may be feeling,” he says. “I research my subjects, and I have a general idea of where I want to go with them. Usually the direction has to do with something from their past, or something going on in their lives. But I bring myself and my feelings to the sessions.”

That goes for his advertising work as well, and because so much of the mood of a Sandro photograph has to do with how Sandro feels, everyone involved—celebrity or model, agency rep or art director—has to trust him.

“When you’re dealing with Michael Jordan or John Malkovich or Dennis Hopper,” he says, “they trust their assistants, agents, the ad agency, or the publication for which they’re being photographed to put them in front of the best photographers. But their trust only goes so far, and I have to build it for myself and by myself from the second that person walks in the door.”

It starts with a handshake, but it’s his two hands on the subject’s one. He intends a welcoming, comforting touch, but also a message: “You’re in a good place here, a safe place, and I’m going to take care of you. We’re going to collaborate to get something beautiful.” The aim is to assure that he would never do anything to embarrass.

On set, Sandro works closely with, and close to, his subjects. “I put my hands on their shoulders or arms to guide them, I touch when I talk, and there’s an energy, a connection, and they feel safe. They feel that I care about them, and they’ll show themselves. Their guard falls, they’re vulnerable, and they are much more willing to give me that beautiful little secret I’m looking for, that little secret in my photographs that makes my viewers want to know even more.”

Available Dark

Sandro—whose last name is Miller, but who is known and referred to industry-wide by only his first name—may manipulate, suggest, and maneuver as he offers a true representation of where he wants to go and what he wants to achieve. But make no mistake: these sessions aren’t visits with friends. He’s friendly, but he’s working.

Because he knows what he’s going to end up with, he’s prepared ahead of time. “I generally have two or three different backgrounds set up, and I’ve usually done my lighting tests. Often I’m given 10, 15, or 30 minutes, an hour at most, so all the tools have to be up and ready.”

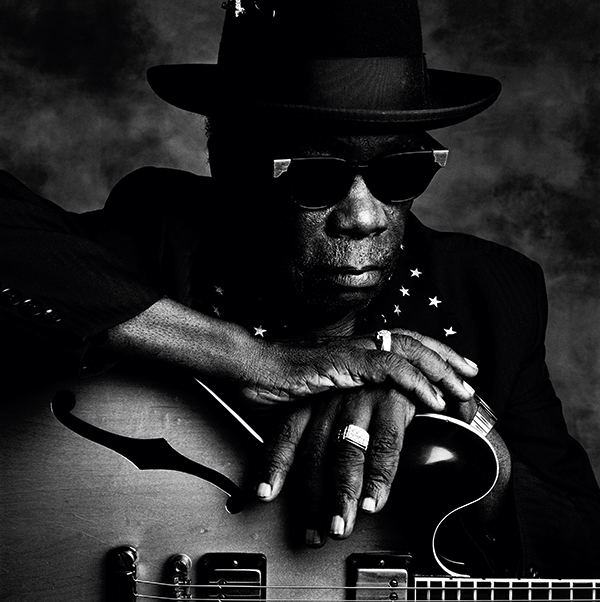

Sandro’s portrait moods don’t often call for high-key, white backgrounds. “I do so much of my commercial work that way, when I get to my portraiture I really want to do something I’m feeling, and those feelings usually come with a medium to dark background.”

There’s a practical reason for that as well. “I can shape my light a little better,” he says. “With a really light background you’ve got bounce, and I can’t get the shape, the sculpture, that I really enjoy for my light. In the dark, there’s a greater range of expression and subtlety in feeling and mood.”

Light Moves

Sandro’s lighting choices run the gamut from the simple to the elaborate. “I can light with a match, a candle, or the biggest lighting setups,” Sandro says. “I’ve been doing it over 40 years, but I never have exactly the same setup. I’m always researching new lights, testing new lights, buying new lights. I love to experiment, to play with light, to really shake it up.”

For an advertising job he’ll test two or three different lighting approaches and show the client, on the morning he walks in, the approach he’s chosen. “I’ll explain why I think we should go with this lighting, but he may have a good reason to say no, and he’ll want something different. I’ll say, ‘Good, let’s do that,’ and we set it up and go to work.’”

With all his experimenting and testing of new lights, when it comes to shooting he says he’s “usually a two-light guy, with maybe a light on the background.” For his strongest portraits, it turns out often to be one light for the subject.

“Constant light, strobe light, light bulbs, fluorescent lights, or mix it all—everything depends on what I’m going for. I just got done with a huge campaign where I used almost all the lights that were available. I got mixed green and purple light that was beautifully effective for the job. Sometimes I just let it go and use a lot of light, but I will still have natural light on my subject so the skin tone isn’t going green.”

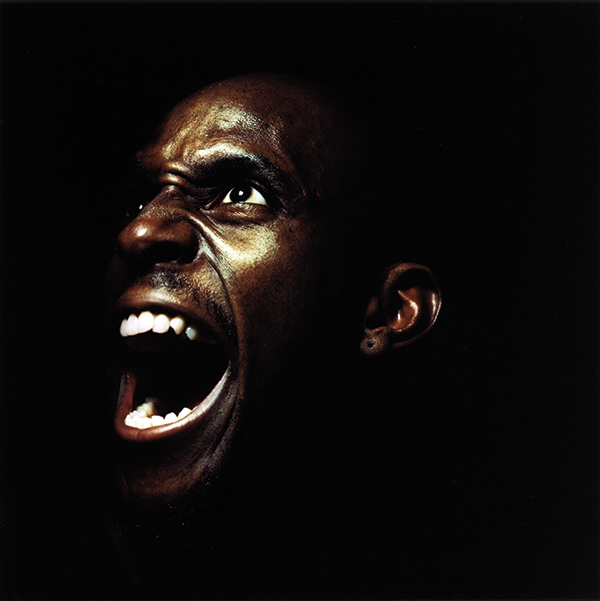

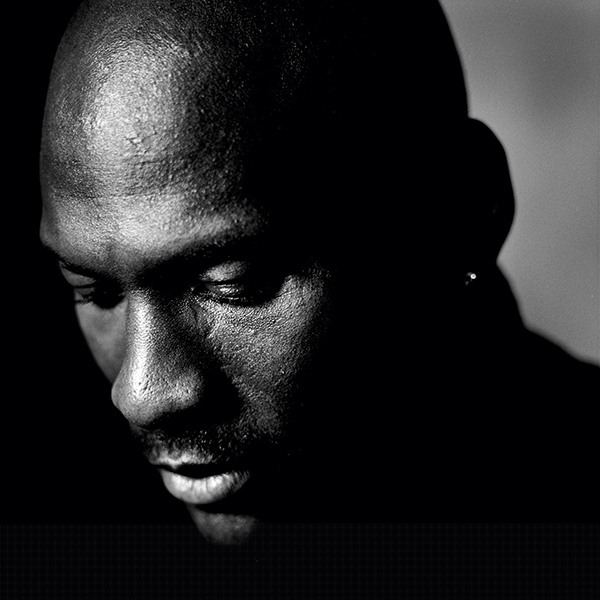

Three Minutes With Michael Jordan

Sandro has photographed Michael Jordan several times, but he made his most iconic and perhaps most dramatic portrait of him in the least amount of time they’ve spent together in the studio.

“Jordan walked in and said, ‘Sandro, I have about three minutes here.’ We did 72 shots—72 portraits—in that time, and for one of them I said, ‘Michael, we have to go to that place, right now, where it hurts the most. You lost somebody close to you just weeks ago…’”

It was Jordan’s father, shot to death by two men who stole his car. Sandro had to know he was as close to the line as he could get. “I said to him, ‘I need you to feel that, to think of that, and of him.’ And he dipped his head and there was a tear welling up in his eye. I took two photographs, and we went on.” Seventy-two images in three minutes.

“Before he walked in, I didn’t know how much time I’d have, but I had it planned out. I’d spent hours setting up the lights, I’d brought someone in who was six-four; it was all done, all ready. And then I put down on paper the emotions I wanted to get, and I rehearsed them, so I wouldn’t have to look at the paper. I had to know where I wanted to go in order to get him to go there with me.”

Respect, care, concern…but not a visit with a friend. There were photographs to be made. This was the job.

Breaking The Barrier

Some of the people he’s photographed have experienced fame and acclaim, but Sandro has to get more from them than what he calls “the okay, I’m here, now make me look good, although I know I already look good” experience.

“I don’t warn them beforehand where we’re going to go,” he says. “I don’t tell them I want them to scream, or dip their head and go to a deeper place. I don’t prep them. It’s all in the way I talk to them during our shoot. I’ll use moments from their lives, something they’ve won, an achievement, or a tough, personal moment to bring them to different levels of emotion—and I’m not afraid to go to those levels, too.” He’ll show the emotion first, go to the place he wants them to be if that’s what it takes to get the photograph. “I can’t ask them to reveal if I’m not going to reveal. I have to make them get it, and I have to know the moment they do.”

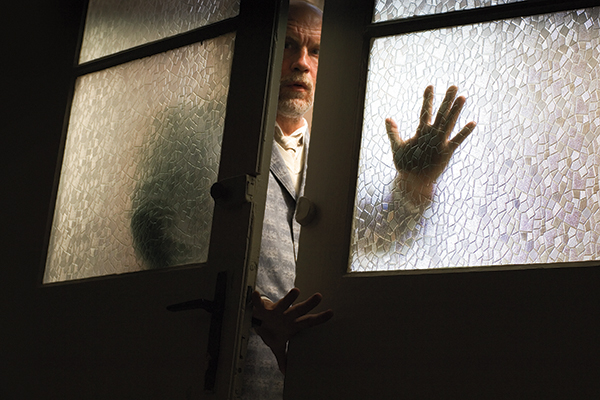

From time to time he’ll have to deal with a person putting up a barrier, an actor giving a performance. “I have a responsibility to whoever I’m shooting for to come up with something special, so I may have to surprise that person, to come back with something that’ll get his attention and let him work with me, not against me. I have to always be prepared for that. What if someone walks in here today and doesn’t want to be here? What am I going to do?”

He’s going to catch them with something he knows or with an unexpected question. “I always have something in my back pocket.” Often that means sharing something about himself—his interests, his personal projects, his concerns.

What he doesn’t want to share are views of the images coming up on the monitors as the session is happening. “We’re all a little insecure, no matter who we are, and I don’t want my subject feeling uncomfortable because he doesn’t like the way he looks. I turn the screens away from him, and if he wants to take a look I’ll say, ‘I’ve got you in the perfect position right now, let’s finish up. I’ll show you when we’re over.’”

Part of the job is keeping his subjects away from their own insecurities.

Personal Challenges

“I have a great advertising career,” Sandro says, “and I’ve always believed in balancing that with personal work.” So he gives himself the assignments no one else gives him. “I’m curious, I want to explore and experience.” And so he travels to Morocco and Papua New Guinea to photograph indigenous tribes. He takes on the breathtakingly audacious project of photographing John Malkovich in spot-on recreations of 35 classic photographs by the likes of Irving Penn, Robert Mapplethorpe, Bert Stern, and Diane Arbus.

These are also things he can talk to his subjects about to get their interest and to show them there’s more to him than just studio sessions. “Sometimes I’ll have one or a couple of my books out, or a couple of images, nonchalantly, on the counter, so they can see them, and that raises a bit of conversation.”

There are, as well, dramatic photographs on display in the studio—dance images, strong portraits from Cuba, celebrities, models—so his subjects can discern his interests, note his accomplishments, and understand they are not in the presence of a get-the-shots-and-get-them-outta-here guy.

“You know what happens then?” Sandro asks. “They get it.”

Sandro’s Gear Box

For studio portraits Sandro primarily uses a Hasselblad H2 body and a Phase One IQ260 digital back and two HC lenses—an 80mm f/2.8 and a 120mm f/4 macro. For environmental portraits on location he’ll turn to a Nikon D810 and a trio of Nikkor lenses: the 24mm f/1.4, 50mm f/1.4, and 85mm f/1.4. He keeps an array of lights and light modifiers to choose from, including a Profoto ProTwin Head, a Profoto ProHead, the Profoto 7a Studio Generator, an Elinchrom Octa Light Bank, Broncolor Para 88 and Para 222 reflectors, Chimera medium and small softboxes, and an 8’x8’ diffusion silk.

Sandro’s photography is on view at his website, sandrofilm.com. Here is coverage of Sandro's popular "homage to photographic masters" project with John Malkovich.

- Log in or register to post comments