Jay Maisel: How a Master Photographer Uses Gesture in Images to Tell a Story

“I really do not consider myself to be a storyteller,” Jay Maisel says. “Pictures are basically anecdotal anyway.” In his studio full of artifacts and mounted photos from his travels around the world, Maisel is happy to reflect on his 63 years of personal and commercial photography work.

Best known for his ability to capture vibrant colors using light and gesture found in everyday life, Maisel studied painting and graphic design at Cooper Union and later at Yale, studying under former Bauhaus professor Josef Albers. A firm believer that one shouldn’t just major in photography, Maisel says one needs to first learn what works visually, “whether it’s a painting, sculpture, architecture, or pottery. Our history of photography did not start with the daguerreotype. It started with cave painting.”

When Maisel was about 20, his brother-in-law loaned him a Kodak 35mm camera. “It wasn’t until I kept on walking out of my painting classes to go out and take pictures that I realized I enjoyed photography much more. And I was always a great believer in instant gratification.”

His first big break into commercial photography was doing work for a large pharmaceutical company promoting Ritalin and other drugs. “I had a capacity for making things look real, which was based on the fact that I was technically inept,” Maisel recalls. “Nothing looked commercial or sharp. I would hire actors—not models—to pose as in a catatonic state or with an aggressive look. After a while I became quite good at simulating what you might see in a mental institution if you could get in.”

Since that time his photos have appeared on five Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue covers, the first two covers of New York magazine, and in numerous advertising and corporate publications. Many assignments involved renting boats, helicopters, and Learjets, and even landing on narrow mountain buttes to get the right shot.

Maisel is famous for his photo of Miles Davis on the cover of the album Kind of Blue. He also had an assignment early in his career to photograph Marilyn Monroe and other celebrities at a party after the release of East of Eden. “I remember her sitting next to Sammy Davis Jr. at the piano and she was in ‘full flirt.’ After taking about 100 great shots, I looked down and realized I did not have 100 frames on the roll of film. The take-up spool hadn’t worked so I was shooting with no film going through the camera. The only photo of her I ended up with was one taken among the crowds out on the street.”

Maisel made the switch to digital in the year 2000 when his friend Sam Garcia, “who knows I’m an anti-technician, forced one into my hand.” Today his go-to cameras are the Nikon D3S and the D4S with a 28-300mm zoom lens.

He does not believe in using Photoshop to change a photograph, but will on occasion use it to lighten an image. “Sometimes you come across a picture where there’s one element that you screwed up, but 99 percent of my pictures are not altered by Photoshop.” He also believes a photographer should crop or frame his image in the shooting, not in postproduction. “You crop or frame the image by moving yourself, or changing lenses, or zooming in or out on the image. If you don’t shoot carefully, you start getting sloppy in your thinking and seeing. You’ll find yourself spending way more time behind the computer rather than the camera.”

Gesture in Storytelling

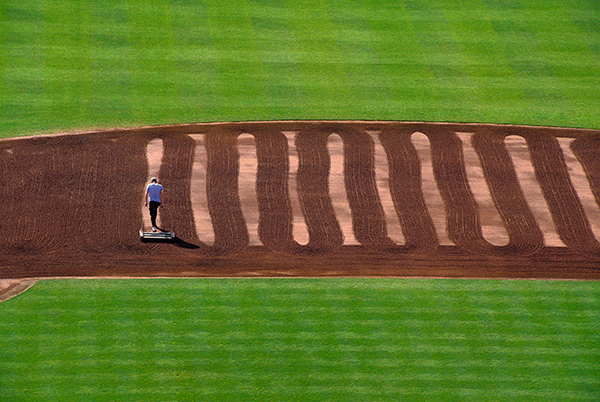

In his book, Light, Gesture & Color, Maisel states that of the three, gesture is the only one capable of carrying a narrative. He uses the word “gesture” as the “expression that is at the very heart of everything we shoot.”

Maisel believes that gesture is “not just the determined look on a face; it’s not just the grace of a dancer or athlete…It exists in a leaf, a tree, and a forest. It reveals the complicated veins of the leaf, the delta-like branches of the tree, and when seen from the air, the beautiful texture of the forest. Gesture gives you a visual story of the essence of what you are looking at.

“It’s important to realize that gesture can be about someone, one who is absolutely still, in repose or even asleep. You can show resignation, sorrow, thought, introspection, delight, acceptance, and more,” Maisel says.

Take, for example, the image of a man in Rome sitting next to the slides and postcards he is trying to sell. “Gesture is not just the man’s expression, his hand on his face or the way he is sitting,” Maisel explains. “Gesture is in the cards and the slides, and that is very different from the gesture in the 400-year-old wall behind him.”

Asking Questions

“I love when pictures ask questions or make others ask questions,” Maisel says. This leads to perception and optical illusion.

He recalls a time when he was viewing a slide he had just gotten back from Kodak and thought, “This doesn’t look like what I shot at all. A little voice came to me and said ‘Turn it over, stupid!’ and I could see immediately what it was. I began to realize I had taken a lot of pictures that if I turned them 180 degrees they look completely different. This is because the brain is hardwired to assume that light comes from above. When light comes in from a different direction, the brain assumes it’s a different shape. Ambiguity can be multiplied if the light comes from an unusual direction.”

Capturing Emotions

When trying to capture emotions in photographs, Maisel shares the following advice: “The best way to capture an emotion in a photo is to try to become sensitive to what’s happening in front of you. Don’t go out with a plan, such as ‘I’m going to shoot a picture of a woman with a red dress, a blue umbrella, and yellow shoes.’ You can be looking for a long time and while you’re looking you’re going to miss everything that’s really there. The less specific the demands you place upon yourself are, the more open you can be to what’s in front of you. Many photographers see things through a prism of their previous success, which is dangerously detrimental to seeing anything fresh in the future.”

Storytelling in a Series

Everyone in New York City was devastated by the destruction of the World Trade Center buildings on September 11, 2001. At the time, Maisel most likely had the largest collection of photos of the twin towers since he had a great view right from his residence in Lower Manhattan. Two weeks after the attack, Maisel worked up the courage to go down to the area to view the collapsed buildings. Without any expectations of what he would see there, he ended up taking pictures of the shock and sadness on people’s faces. Called “Bearing Witness,” the 58-photo series poignantly tells the story of the horror of that infamous day. “It’s probably the most powerful thing I’ve ever done,” Maisel says.

For 49 years Maisel lived in the former 35,000-square-foot Germania Bank built in 1898 in Lower Manhattan. Purchased in 1966 for $102,000, the mansion contained 72 rooms over six floors. From various windows and the rooftop, Maisel took photos of everyday life in the Bowery, and has assembled a collection he calls “Bankview.”

Not ready to rest on his laurels, Maisel now has the luxury of time to go through his large collection and he plans to publish several books: Away, showcasing his travels throughout the world; Home, featuring photos from the bank; Amanda, showing photos of his daughter “with or without her permission”; and Jaywalking in New York.

Maisel’s advice for those looking to capture a gesture or tell a story through photography is to “never lose your curiosity, and to think about what you are shooting before you shoot it. When you see the right moment you will know. And as Ernst Haas once said, ‘You do not take pictures, you are taken by pictures.’ So allow yourself to be taken by pictures.”

Additional photos can be viewed at jaymaisel.com and in his books, Jay Maisel’s New York; It’s Not About the F-Stop; A Tribute; New York in the ’50s; On Assignment; and Light, Gesture & Color.

- Log in or register to post comments