After The Shoot

Editing Is A Mist For Digital Photography

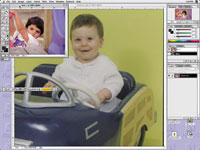

Even if you have vowed to

never get involved in the digital imaging revolution, you've got

to admit that you probably are amazed at some of the seamless things

that can be done with photo editing programs like Adobe Photoshop. |

|||

Choose Your Weapon.

Which image-editing program to purchase? If you ever wanted to get into

the graphic arts business for real, then you're pretty much chained

to the industry stalwart, Adobe Photoshop. It's the biggest, most

expensive, and the most pervasive in the graphic arts industry. |

|||

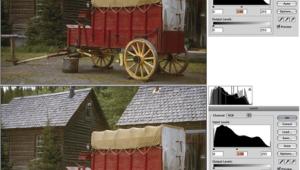

Do you remember the exact day

when you could actually "see" the final image in your head

before you even brought the camera up to your eye? Well, you've

got to develop that same sense of visualization with the digital medium.

I've found that small images intended for web usage can be almost

absurdly high contrast, since the dynamic range of a computer monitor

is far less than that of a photo print or magazine page. Once you've

run enough color prints through your printer you'll begin to understand

the tendencies of your printer and alter both your shooting and editing

style. Since all point-and-shoot digital cameras do substantial enhancing

in the camera, you've got to try and always capture as much raw

information as possible. Once you've achieved a pure white or a

pure black in the digital world, there is no more information, so it's

super important to keep your exposure in the safety zone. I use a point-and-shoot

camera that has a very neutral color balance and doesn't do a lot

of in camera processing. While some have complained about the lack of

"punch" in the images, I like the ability to fix it myself

later, without the camera introducing extra noise or maybe even clipping

the black or white points without my knowledge. Once you know how your

camera and final output device responds, you can make those decisions

during the shoot. |

|||

Luckily for digital imagers,

you can establish a pretty foolproof "standard' right in your

computer. I keep a handful of very small files saved in the "Stan-dards"

folder on my Macintosh. I keep a bright sunny outdoors scene, a handful

of headshots in different light sources, and a couple of product shots.

I have found that even with all of my experience my eye can get fooled

by the monitor, room lighting, subject matter, etc. I'm almost embarrassed

to admit how many times I've delivered beautifully packaged CDs

of images to clients who then had to increase the contrast in order to

bring up the black or whatever. It's a subjective world we live

in, so I like to establish standards. Here's how: take the photos

that have pleased you the most when output, you know, the shots of your

kids that printed up beautifully, the still life shots that looked great,

you choose. Then shrink them down so that they only take up a few inches

of screen real estate. On a 1280x960 monitor that's about 320x240

pixels. I save them as JPEG images and name them "Portrait 1,"

"High Key Product 2," etc. When I'm editing an image,

I pull up the sample and let it sit next to my image while I'm working.

I match the flesh tones and overall gamma of the scene, so I know that

I'm working in a color environment that has proven to work in the

past. |