Shock Value: Documentary Photographer Nina Berman Opens Our Eyes to the World

This is the cover shot for Nina Berman’s book Homeland, in which she documented post 9-11 America, focusing on the militarization of American life. Berman used this air show in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to direct attention to military spending at the expense of our civilian infrastructure, as evidenced by the surrounding urban decay and body language of the beachgoers as the military aircraft passes overhead.

All Photos © Nina Berman

Documentary photography captures the truth but it also tells a story. And that is exactly what Nina Berman has always aimed to do, and what she succeeds in doing, as the Brits say, so brilliantly. Her pictures evoke our emotions; they often shock; but they never fail to open our eyes to the world around us.

Comfortable in Her Skin

Documentary photography and photojournalism both chronicle reality. But where do we draw the line between the two? Berman noted that “both documentary photography and photojournalism seek to ask questions. In differentiating the two, I see it more as how people identify themselves. I started calling myself a documentary photographer when I started working independently, self-initiating long-term projects.

“Also, when I was coming up in the profession, the typical image of a photojournalist was a guy with a lot of cameras, wearing certain kinds of clothing. So I wanted to call myself something other than that. I also think that there’s a sense that it’s okay for a documentary photographer to express personal opinions in their photographs, rather than being objective, which the photojournalist must be.”

Pictured here is a law student screaming “Bomb Iraq” at a pro-Iraq War rally in Times Square, held a couple of days before the war began. It was also featured in the Homeland book.

From Print Journalism to Photojournalism

Berman didn’t start out shooting stories. She, pure and simple, wanted to be a print journalist—a writer. “But, when I was 17, my dad gave me a camera and I started taking pictures.” Something then clicked for Berman, no pun intended. “After grad school, I got a job as a writer, and I felt very trapped being tied to a phone and a desk. I felt that working with the camera would be more freeing.”

Professionally, Berman shot her first photo story while working as a reporter for the Bergen Record. “I did a project where I accompanied a group of veterans returning to Vietnam. After the story was published I distributed the photos through an international picture agency, leading to further publication, which made me think that I could make a living doing photography as a freelancer. That project also had a great impact on how I would look at things moving forward.”

This is a shot of the security wall at the Za’atari refugee camp the day after it was installed. The images represent the work of several NOOR photographers. Berman produced and also shot for the project.

A Lifelong Passion

Berman’s passion for documentary photography is unwavering. “I still shoot documentary photography today because I find it the most interesting, most exciting, most profound way I can think of to interact with the world. It still carries a huge amount of discovery for me. That thrill of going to places where you’ve never been, talking to people and trying to understand their situation is still completely captivating for me.”

She continued: “I feel as if I’m always learning, not just learning how to photograph, but learning about the world around me. I’m very much of a politically motivated person, so I want to understand the history of my own country and how power is manifested and I want to understand people’s struggles. So those are the things that motivate me thematically. Visually it can be a whole host of things, but always contingent upon the story.”

Berman is working on several projects concurrently, switching back and forth as circumstances and the muse dictate. One key project focuses on the aftermath of war. “My story is about military weapons production and testing in the United States from 1945 onward—what that’s done to the landscape and communities. So I’m looking at everything from the Trinity bomb test in New Mexico to Agent Orange production in Newark, New Jersey. I’m going to Indiana to look at how former military bases are being turned into wildlife refuges. It’s a very different kind of American road trip.” She received the 2016 Aftermath Project award grant to fund the work.

This portrait of Spc. Robert Acosta was featured in Berman’s book Purple Hearts, which focused on 20 severely wounded veterans from the Iraq War. The book received worldwide recognition.

A Reason to Get Up in the Morning

While reflecting on her career, Berman offered this observation: “One of the things that’s so sad about the decline of magazine photography today is that in the past an assignment could kick-start a personal project, or lead a photographer to an idea they might not have had on their own. There has been so much great work which started that way, but those opportunities are fewer now. So it requires the photographer to be a lot smarter, a lot more of an independent thinker to figure out what they can do in the long term that’s going to be relevant and gratifying.

“The best work takes time, people need to think about it, and maybe they stop for a while, then they pick it up again. That’s the work that lasts. I want my work to have some kind of social impact. I want it to reveal something that maybe isn’t being discussed. So that gets me up to do the work I do.”

This is a gun-rights rally at the Alamo in San Antonio, Texas, in 2013. “It’s my take on the gun culture in the United States. What intrigued me was the mix of diehard gun owners and characters from pop culture in the crowd, together with the little boy, who was focused on me.”

The NOOR Collective

One of the driving forces behind Berman’s work today revolves around NOOR Images, a combination photo agency and foundation. It is a collective of talented individuals who seek to “contribute to a growing understanding of the world by producing independent visual reports that stimulate positive social change and impact views on issues of global concern,” according to the website noorimages.com.

One body of work that grew from her membership in NOOR was the Za’atari project, in 2014. “Za’atari is a large camp housing Syrian refugees in northern Jordan. I had an idea to turn the 100-meter security wall into a large photographic mural showing images of the camp’s residents. It was an attempt to call attention to the humanity of the people inside the camp. I took three NOOR photographers with me, Stanley Greene, Andrea Bruce, and Alixandra Fazzina—we had all previously worked in refugee camps. Along with the mural, we set up a photo booth and made hundreds of portraits for camp residents. It was a unique experience, and an attempt to work beyond journalism platforms and work more collaboratively to give something back.”

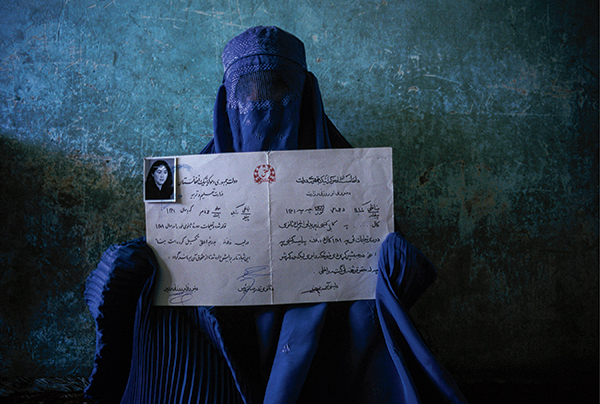

“On assignment for Newsweek, I was one of only a few photographers shooting inside Taliban-controlled Afghanistan at the time (1998). The story was about how women were managing under strict Taliban restrictions.” This woman is displaying her vocational school diploma, revealing ambitions that were no longer tolerated.

This was shot at the 2016 Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio, after the balloon drop, moments after Donald Trump accepted the nomination. Berman was assigned to cover both the RNC and DNC for Columbia Journalism Review. “I like the mystery revolving around this shot.”

Not to Be Dissuaded

While working as a photojournalist, Berman found it disheartening that stories she’d worked on hadn’t had the impact she would have liked. She’d shot stories in Afghanistan, Bosnia, Mexico, and India, often photographing women in horrendous situations. But, after some time, she was forced to change her methodology. “The women I met thought that my presence was going to change their lives, and I knew that it wouldn’t. I knew that a double-page spread in Newsweek would not make much of a difference. And even though I explained that to them, and even though I felt that the story and photographs were of value, I started to feel that I needed to work in another way.” That other way led her to pursue long-term projects, with subjects who wanted to tell their story, “where my photographs could go beyond just a magazine publication. Which is one reason why I got involved in this Za’atari project.”

Berman has received generous praise for her work. But there’s always a yin and yang to every compliment. “I received some nasty comments over my Purple Hearts book when it came out, as well as abusive e-mails. That just means that I’m doing something good.”

As is obvious, Nina Berman isn’t afraid to step into the lion’s den to capture the naked truth with her camera. Something indefinable keeps driving her. Perhaps it’s her own longing to reveal how unjust the world can be. Perhaps it’s simply that strand of DNA that defines her as a documentary photographer. Whatever it is, we’re thankful to her for taking us to places and meeting people that would have easily escaped even our peripheral vision.

This scene occurred at the funeral of Jose Luis Lebron, a young man who was killed by a New York City police officer. These are his family and friends, one of whom collapsed after the funeral. Berman points to this shot as the launching pad for a series she’s been working on focusing on police violence.

What’s in Berman’s Gear Bag

* Nikon D810

* Nikon D750

* Nikon Nikkor 50mm f/1.2 lens

* Nikon AF-S Nikkor 24-120mm f/4G ED VR lens

* Nikon AF-S Nikkor 28mm f/1.8G lens

* Nikon SB-700 AF Speedlight

* Fuji X100T

* Azden Mic (for video)

Berman’s Favorite Piece of Photo Gear

The Nikkor 50mm f/1.2 lens is Berman’s favorite piece of photo gear. She says, “It’s such a beautiful lens, just looking at it, I mean even before I put it on the camera. I don’t use it that much but, when I find a moment or want to break out of my standard shooting style, I’ll put it on. It gives me a renewed sense of possibility.”

An associate professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, Nina Berman operates out of New York City. To see more of her work, visit ninaberman.com.