Capturing the World's Amazing Masks: How Chris Rainier Tells Stories with His Camera

(Editor's Note: This story also appears on ROAM, a website that features the images and stories of outdoor adventure.)

To say that Chris Rainier's main subject as a documentary photographer is vast would be an understatement. Much of Rainier's work these days focuses on documenting the lives and cultures of indigenous people around the world.

But how does one go about trying to capture such an immense topic, one that has taken Rainier from the steppes of Mongolia to the jungles of South American to the deserts of West Africa? The key, for him, is to pay attention to the details.

In his 2004 book of photographs, "Ancient Marks," it was the tattoos, scarifications, piercings and other forms of body art that Rainier documented with his camera. The book was the result of seven years of travel to seven continents and thirty countries, with Rainier photographing tattoos and body markings of men and women from places as far flung as Brazil to New Zealand to the barrios of Los Angeles, and many other locations in between.

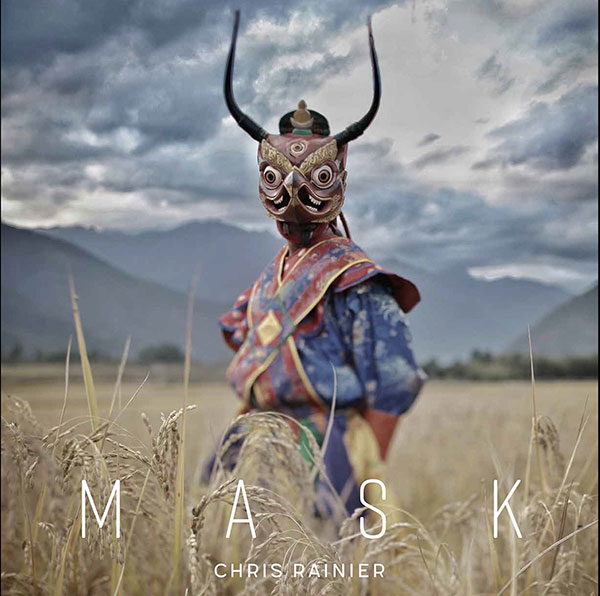

Now Rainier is back with another book of photos that focuses on the striking details of indigenous and endangered cultures. Titled "Mask," the book features more than 130 images of traditional and modern masks that Rainier, once again, photographed during his exhaustive travels to, seemingly, the ends of the earth.

Mask: The Book

In "Mask," Rainier shows us the otherworldly masks of tribesmen in Burkina Faso, which are used during initiations rituals; the rarely seen, animal-like Bön Buddhist masks from a monastery in Nepal; and the more familiar (to western eyes, at least) raven and bear costumes of Native American tribes in North America.

With their heavily desaturated colors and disorienting shallow depth of field (Rainier, at times, uses tilt-shift lenses), his images can be beautiful, surreal and frightening all at once. In particular, his shots from the Austrian Alps of the Krampus masks, which were literally designed to terrify children, will make the hair on the back of your neck stand up.

In a bit of happy coincidence, I recently interviewed Rainier about his work and career on what turned out to be Indigenous Peoples' Day (also designated as Columbus Day, but that's another story) and he explained that the singular focus of his images can be traced back to his time spent assisting Ansel Adams.

In the 1980s, Rainier was Adams' last photo assistant, working with the master photographer and environmentalist for about five years before Adams' death. One of Rainier's main jobs with Adams was proofing and printing more than 50,000 negatives from Adams' archive.

"I learned a tremendous amount about the evolution of an artist: the risks, the successes and the failures," Rainier says. "I also learned a lot about how important it is to get to know your subject. He had this intimate relationship with light, texture and clouds, and that can only come from time spent."

Ansel Adams' Influence

Another big influence was Adams' commitment to conservation and his efforts to use art and photography as a social tool to help preserve the National Parks which, at the time, were endangered. Adams' work with the Wilderness Society and the Sierra Club also made an impact.

Rainier himself is the founding director of The Cultural Sanctuaries Foundation, a global charitable organization that focuses on preserving biodiversity and traditional cultures, and co-founder and co-director of the Enduring Voices Language Project, a program that puts technology in the hands of indigenous cultures to help them preserve their languages and traditions.

As a National Geographic Fellow, Rainier currently directs the All Roads Photography Program, which funds indigenous photographers and provides them with resources to help them succeed in their careers.

Rainier also credits Adams with teaching him that there's an important business side to making art and that if you want to sustain a career, you need to consider your audience without pandering.

"In visual communication, you have to have something that's appealing," he says. "I remember Ansel saying: 'I'm not going to photograph all the deforestation and destruction of the wilderness.' His philosophy was there's so much beauty in the world, so many amazing things, and he wanted to celebrate that. For me, I want to celebrate cultural diversity. In a world where happiness is under bombardment every single day, and loss and degradation seem to be theme, it's important to emphasize that we live on a remarkable planet."

Splitting His Focus

Rainier has photographed his fair share of "loss and degradation" over the years. While working as a photojournalist for TIME magazine, LIFE, the New York Times, and the National Geographic Society, along with many other publications, he photographed the war and eventual break-up of the former Yugoslavia, the destruction of lower Manhattan on 9/11, and the devastation and tragedy of the 2004 earthquake and tsunami in Indonesia.

He describes switching between doing his artistic documentary work and his conflict photography as almost like having a "split personality."

"I'd go off to a war zone and I'd show up with a Diana camera and black-and-white film and the other photojournalists would go: 'What are you doing here, you're supposed to be in Yosemite," Rainier recalls.

While he doesn't do as much of the hard-edged photojournalism as he used to, his itinerant life remains. And it seems like a natural fit for Rainier, who grew up the son of a South African oil businessman and a Canadian artist mother, traveling extensively as his father's job took the family to Africa, Australia, the Middle East and then eventually the United States.

"You've heard of an army brat, well I was an oil brat. Wherever the oil was flowing, we went," he says. "It was a fantastic opportunity to see the world and get exposed to new cultures."

Storyteller with a Camera

His father was a passionate amateur photographer who gave Rainier his first camera. "He put a Kodak Brownie in my hand and I just fell in love," he says. "I ended up jury-rigging a darkroom in my bathroom. We'd go to the Australian outback and I'd photograph unusual trees, wildlife, landscapes. I was fascinated with people, talking to people, and taking pictures of anybody that was crazy enough to get in front of my camera."

Rainier calls himself "a storyteller with a camera," rather than a photographer, and it's an apt description. He says the notion came to him while sitting around a fire in New Guinea – where some of his early documentary work took place – and realizing that of the over 6000 languages in the world, more than half exist only orally, there is no written form.

"Photography is a visual storytelling mechanism and this is what my life is about" he says. "Humans inherently love to tell stories. We meet someone, find common ground, and tell stories. And photography is a powerful communicator. A hundred years from now, someone will look at this image of a crocodile dance and say, hey, we can do that dance again now. Photography can be a great revitalizer."

Chris Rainier is a judge in the first annual ROAM Awards, which showcases adventurous photographers, filmmakers and writers. Find out more about the ROAM Awards here.

You can buy Rainier's book, Mask, on Amazon here.