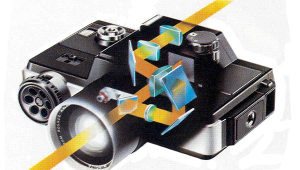

Pontiac Bloc-Mtal 45; If You Can’t Afford A GTO, How About A Camera?

Sixty years is a long time, and it is easy to forget how different life was in those days. In particular, the normal format for snapshots was a black and white contact print just 21⁄4x31⁄4” (6x9cm nominal, 8-on-120 or 620). Enlargements (except “en-prints”) were rare and expensive, and in any case, many of the films of the day were grainy and unsharp when enlarged more than 3-4x; some were not too good at 2x.

|

|

|

The equivalent of today’s digital compact was the fixed focus, fixed speed box camera with a lens of f/11 or less. The “bridge camera” of the day—the one that offered a bit of control to the user, such as variable shutter speeds and apertures plus focusing—was the 6x9cm folder.

It is important to remember all this when considering the very French Pontiac Bloc-Métal 45, introduced in 1945 as a replacement for the Bloc-Métal 41 (of ’41), itself a vast improvement on the original Bakelite Pontiac of ’38. The “Bloc-Métal” name referred to the solid metal construction. Despite the name and the date of introduction, actual production for sale seems not to have started until ’46.

|

|

|

The main differences between the Bloc-Métal 41 and the Bloc-Métal 45 were the available lenses and shutters, plus the fact that the 41 had both a folding finder on the body and a waist-level “brilliant” (or possibly reflex) finder on the front standard, while the 45 had an average squinty built-in reverse-Galilean finder only. Apparently, too, the plating on the 41’s brightwork was nickel, while on my 45 it is definitely chrome.

The entire life span of the Pontiac’s manufacturer MFAP, the Manufacture Française d’Appareils Photo, seems to have been well under 20 years, from its foundation by M. Laroche in ’38 to its closure some time in the ’50s; possibly as early as ’52. One of their last cameras, the 35mm Baby Lynx, was allegedly made in French Morocco, though I have this only from a secondary source which contains other mistakes, including that the 45 takes 120 film instead of 620. It won’t: I tried.

|

|

|

Not without reason, the Bloc-Métal 45 is often regarded as the most beautiful of all folding cameras, not least by the French themselves—who, incidentally, use the term “un folding” for what we call a folder. Constructed from cast aluminium alloy, it really does look gorgeous, especially if you polish it up with Solvol Autosol to remove the dull gray oxidation of at least half a century: the last 6x9 Pontiacs seem to have been made in ’52, though 35mm cameras from the same company may have survived a little longer.

The elegantly sculpted top plate is its most striking feature, with its integral accessory shoe and rotating depth of field scale. If you don’t believe that an accessory shoe can be a thing of beauty, all I can say is, look at the Pontiac. But the 45 is a harmonious whole, from the curved folding leg on the front panel or bed (which doubles as the lock) to the shutter bezel, the black-and-aluminium detailing on the exterior, the red-filled engraving on the spring-loaded carrying handle, and of course the chrome self-erecting struts.

|

|

|

A particularly elegant detail that I do not recall seeing on any other camera is a retracting body release on the top plate. When the camera is folded, it is flush with the top plate. Open the door, and the button rises to the operating position; close it, and it disappears again. Another delightful detail is what appears to be a storage clip for a cable release, complete with swiveling cap, inside the base plate.

The whole thing is a series of nicely finished die castings: the body, the top plate, the back door, the bellows bed, even the handle, the sliding catch for the back door, and the flip catch for the bellows bed. The bellows are mitre-corner black leather and the red window for the film advance is guarded by an internal, spring-loaded shutter, so you have to push a button on the back to see the numbers when you are winding on. This is of course a safeguard against light strike through the backing paper with the increasingly super-speed panchromatic emulsions of the day, some as fast as ISO 200 equivalent. Intriguingly, the winding knob is engraved “Made in France” (in English), which shows the importance attached to the export market.

|

|

|

Something which does not accord with any history I have seen of the camera is that the body on mine is paneled with either leather or top-quality leatherette, though it has faded somewhat and gone a bit green. All accounts I have read refer to black paint instead of body covering, but the fit and finish suggest that the covering on mine is original—though the lack of any blind stamping (for example, with the manufacturer’s or model’s name) admittedly suggests the contrary. Then again, the very last model of Bloc-Métal 45 with its Gitzo Zotic-1 shutter was reputedly leatherette-covered, so this may have been a transitional model.