How Robert Frank’s “The Americans” Changed Photography: Another Look at a Classic Photo Book

In 1955, armed with a couple of Leicas, several bottles of French brandy, and hundreds of rolls of film, the photographer Robert Frank set out on an odyssey to look for the soul of America. Behind the wheel of his black Ford Business coupe, he drove over 10,000 miles of endless highways and forgotten back roads; and made nearly 27,000 photographs. From these road-trip images he created a “photobook,” a work that has had a profound impact on photography and photographers ever since: The Americans.

Today as Frank enters his 91st year, he is receiving many honors. The National Gallery of Art in Washington is celebrating his work with an exhibition titled From the Library: Photobooks after Frank. The exhibition continues through February 7, 2016 and explores how The Americans opened the way for other “photobooks” and propelled a new a generation of young photographers, like Garry Winogrand and Joel Meyerowitz onto their own journeys. Earlier this year, the New York Times celebrated Frank’s work in several articles calling him “…the most influential photographer alive.”

Robert Frank was born in 1924 into a middle class household in Zurich. During WWII he was sequestered away from conflict by Switzerland’s neutrality and it was then that he discovered photography. It changed his life. “I liked images. Images were natural to me and I wanted to make images and I didn’t want to go to school, I didn’t want to do anything else,” he said.

In 1946 he produced his first photo book, a handmade portfolio called 40 Fotos. The next year he left Switzerland and arrived in New York where his first stop was Times Square.

‘‘The crowd! The crowd! I never was used to such a big crowd, and they were so enthusiastic about being there. It was America! Those big signs!’’ he recalled.

Frank got a job as a fashion photographer for Harper’s Bazaar, but soon set off to travel and photograph in South America and Europe. Returning in 1950, he met Edward Steichen, the director of the Museum of Modern Art’s photography department, and showed him his portfolio. Impressed by the work, Steichen invited him to participate in a group show at the MoMA called 51 American Photographers. This same year Frank married his first wife the artist Mary Lockspeiser with whom he would have two children; Andrea and Pablo.

Also around this time Frank discovered the work of Walker Evans, one of the Farm Security Administration photographers. Evans had documented the ravages of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression and Frank was drawn to the loneliness he captured in his images of rundown buildings and derelict spaces.

Evans lived on the Upper East Side and Frank made a point of meeting the older photographer. They became friends and soon Evans was his mentor and biggest supporter. When Frank expressed a desire to travel and photograph America as Evans had done, Evans suggested he apply for a Guggenheim Fellowship. In a letter of recommendation to the Guggenheim selection committee Evans called Frank, “a born artist.”

Down that Long Lonesome Highway

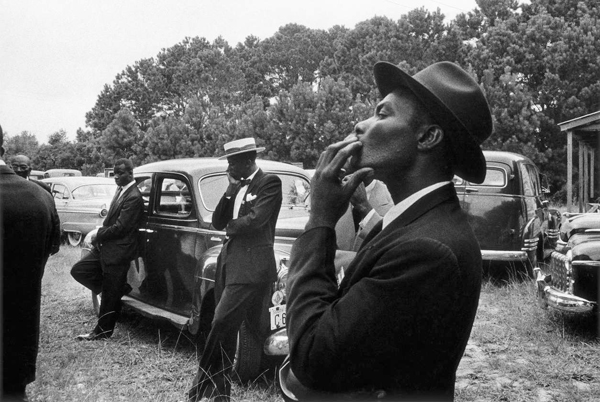

Frank got the fellowship, loaded up his Ford coupe and set off to look for America. Like many Europeans, the thrill and excitement he had felt on his arrival had worn off as he encountered Americans who were struggling just to survive. Frank could not understand how a rich and powerful nation could leave so many of its citizens behind. Frank may have initially seen his road trip as a chance to document these marginalized Americans but as he began to shoot he began to see it in a broader context. It was to be his poetic vision of a hidden America.

Staying in shabby motels, eating in the greasiest of greasy spoons and drinking in desolate bars by the ghostly light of jukeboxes, Frank found this “other” America in the shadows of abundance. Always moving, he drove through a dreary landscape of shuttered towns that had barely survived the dust laden winds of the 1930s that were now bypassed by the new interstate highway system.

Frank photographed parades, holiday gatherings, shiny cars and gigantic flags; but there’s an emptiness that clings to these images. No one smiles and even when a subject catches the photographer taking their photo, their face remains disinterested and blank. Surprisingly nearly a quarter of the images in The Americans contain no people at all as though Frank is saying that life is so hard and unforgiving that even the landscape rejects the people.

‘‘I felt like a detective or a spy. Yes! Often I had uncomfortable moments. Nobody gave me a hard time, because I had a talent for not being noticed,’’ Frank explained.

Getting Printed

Returning to New York, Frank ruthlessly edited his thousands of images down to a portfolio of a little more than eighty images. He took this around New York looking for a publisher but everywhere he went he was harshly rejected. The work was seen as too disturbing and too unpleasant for 1950s tastes. Popular Photography magazine, for instance, belittled his pictures for their "meaningless blur, grain, muddy exposures, drunken horizons and general sloppiness." LIFE publisher Henry Luce disapproved of their lack of “rectangularity.”

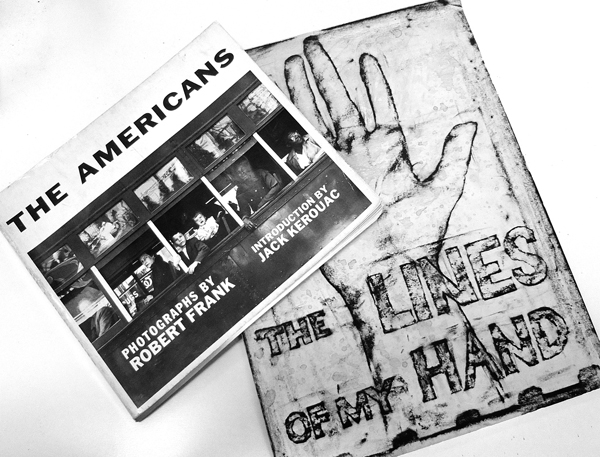

Finally in 1958, Robert Delpire, a Paris publisher, agreed to print the photos as Les Americains and a year later Grove Press republished it in the U.S. as The Americans. This American edition included an introduction by Frank’s friend, the Beat poet, Jack Kerouac and that helped its sales; a little. But the book didn’t do too well as once again Frank’s photographs were roundly criticized. “When it first came out people thought that this was an anti-American story,” he recalled. “It took ten years for that to change.”

What changed in ten years, of course, was America. The 1950s had been an exuberant time when veterans returning home could go to college on the G.I Bill, move into the suburban developments like Levittown and buy big cars with huge fins. Frank’s images of a soulless, violent and racist America simply didn’t jibe with this vision.

In the turbulent 1960s with its assassinations, violent street protests and a new war, the old optimism had died and Americans now saw their nation in a different light. When The Americans was reprinted in 1969 in an inexpensive paperback edition (Aperture, NY) a new audience of young photographers (like me) snatched it up.

We pored over Frank’s moody images that now resonated powerfully with our own disenchantment and despair. In today’s photojournalistic climate, Frank’s intent to show a dark America might be considered manipulative and inappropriate, some sort of “poverty-porn.”

Yet photojournalistic objectivity never interested Frank. The Americans is about his journey and his feelings of disillusionment in discovering that the American dream seemed to be just a flag draped chimera.

The Lines of My Hand

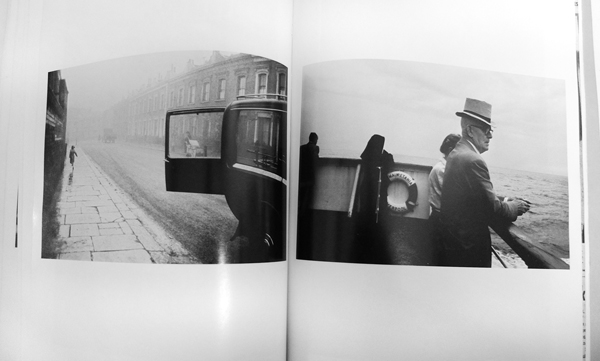

Frank published his second photobook, The Lines of My Hand (Lustrum) in 1972 and it was another very original publication. A photographic autobiography, its pages are filled with dozens of photos sometimes presented individually, sometimes packed into photomontages. Lines didn’t sell well in part because of this radical layout but the images in it are a far cry from the moodiness of The Americans. In Lines there is life and energy. Parisians dance in the street and stolid Londoners somberly walking to work in top hats and “brollies.”

With the re-release of The Americans, Frank pretty much stopped taking still photographs and moved on to making “indie” movies with some of his old “Beat” friends like poets Jack Kerouac and Alan Ginsberg. In the early 1970s he bought a cabin in Nova Scotia and since then he and his second wife, the artist June Leaf, have split their time between it and their New York loft.

While Frank is being praised for his influence and importance today, it was Kerouac in his introduction to The Americans who wrote what is probably the best description of Frank. “Robert Frank, Swiss, unobtrusive, nice, with that little camera that he raises and snaps with one hand he sucked a sad poem right out of America onto film, taking rank among the tragic poets of the world.”

- Log in or register to post comments