Minolta’s Early 35mm Rangefinders Gave Leica a Run For Its Money

All Photos © John Wade

Mention Minolta to pre-digital photographers and thoughts turn to high quality, often revolutionary, 35mm Single Lens Reflex (SLR) cameras. It was Minolta, for example, that introduced the XD-11 (known as the XD-7 outside the US) in 1977, the first camera to feature both shutter- and aperture-priority modes. And it was Minolta that launched the Maxxum 5000 (Minolta 5000 outside the US) in 1985, the first SLR to feature body-integral autofocus.

But go back to the 1940s/1950s and you’ll discover a prestigious range of Minolta 35mm rangefinder cameras that rivaled and, some would argue, bettered the Leicas of the time.

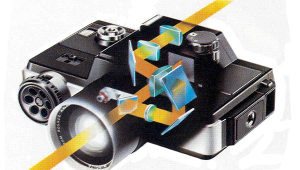

Quick pause for an explanation for those unfamiliar with rangefinder cameras. The term refers to a model whose viewfinder, or sometimes a separate eyepiece, incorporates a system of mirrors that interact as the lens is focused to identify the correct camera-to-subject distance, as an aid to accurate focusing in non-reflex cameras.

It was Leitz that popularized the style in a 35mm camera with the introduction of the Leica II in 1932. However, by 1947, when the first Minolta-35 camera was launched, the Leica IIIf was on the market.

Model I And Model II

There were two basic models of the Minolta-35 rangefinder, and some variations within them. Apart from minor cosmetic changes, the variations in the Minolta Model I camera chiefly concerned the image size. Leica had previously set a standard of 24x36mm, which was followed by most 35mm camera manufacturers. But the Model I, progressing through six variations, began with a 24x32mm image, moved to 24x33mm and then on to 24x34mm. The company eventually adopted the more traditional 24x36mm format with the launch of the Model II in 1953, of which there were two versions with very minor cosmetic variations.

We are going to compare the first version of the Model II with its contemporary, the Leica IIIf. There were some manufacturers who unashamedly made complete Leica copies. The Minolta-35 was not a Leica copy as such, but it did show strong influences from its German rival.

Minolta Vs. Leica

At 5.25 inches, the Minolta was the same length as the Leica, but stood a quarter of an inch higher. Comparing the top plates of the two cameras, you can see the obvious influences: film wind knobs, shutter releases, shutter speed dials, rangefinder housings, and rewind knobs were all in similar positions. The Minolta’s shutter release, however, was raised slightly above the wind knob and speed dial on either side, making the camera easier to use than the Leica, whose release button fell below the height of the other controls.

The Leica won out on its top shutter speed of 1/1000 sec, against the Minolta’s 1/500 sec. On both cameras, speeds from the fastest to the slowest practical for hand holding the camera were set on the top plate dial. Then,with that dial at its slowest setting, another knob on the front of the body was used to set slower speeds down to one full second.

On each camera, the speed dial revolved as the film was wound, and the speeds could not be accurately set until the film was fully wound and the dial reached its maximum rotation.

The Minolta beat the Leica in having a delayed action control right from the earliest model in 1947, which the Leica wouldn’t see until a late version of the IIIf in 1954. The Minolta also had a longer rangefinder base (the distance between the two rangefinder windows), making it more accurate. The visual aspect of the rangefinder, which involved turning the focus control until two images coincided, was conveniently combined with the Minolta viewfinder; the Leica used separate windows for viewing and rangefinding.

The Leica had a collapsible lens that had to be pulled out at the end of a short tube before exposure, and if the photographer forgot to do that, the picture was ruined. The Minolta used a fixed lens that was always positioned ready for shooting.

The Minolta also beat the Leica for film loading. Right from the start, Leica had featured a system in which the film was threaded from the cassette to a take-up spool outside the camera, and then the two pushed up into the body by way of a removable base plate. The operation was fiddly at best and prone to problems if the film did not attach correctly to the take-up spool. By comparison, the Minolta simply used a back that swung open, which made loading the film far easier and much more conventional.

Identical Lens Mounts

Maybe the most important feature shared by the two cameras was the lens mounts, which were identical. The Minolta therefore accepted, and could be used with, then current Leica lenses, of which there was a large range, covering focal lengths from wide-angle to telephoto. The range of Rokkor lenses, made for the Minolta, was a lot more modest: 45mm f/2.8, 50mm f/2, 85mm f/2.8, 110mm f/5.6, and 135mm f/4.

When extra lenses were used on any rangefinder camera, they needed to be combined with separate accessory viewfinders. This was the case with both the Minolta and the Leica cameras. However, longer focal lengths, unavailable in Minolta’s Rokkor range, were often likely to be used on the Leica with a Visoflex, an attachment that screwed into the body, incorporated an eye-level or waist-level viewfinder, and effectively turned the camera into a single lens reflex.

Using Leica lenses, the Visoflex could also be used on the Minolta, although, when screwed into place, it was fouled slightly by the delayed action lever and slow speed shutter dial. As this prevented the device from being screwed completely into the body it would have been okay for close-up work, but might have affected infinity focusing.

So who won out in the end—the German Leica, or the Japanese Minolta? The Minolta certainly won on price. In 1953, a Model II with an f/2.8 lens cost $150, against a Leica IIIf with an f/2 lens at $348. For some features and ease of use, the Minolta might also have had the edge. For lens range, the Leica won hands down. Then, there’s the durability factor. Find a Leica IIIf today and there’s a good chance the shutter is still working. A Minolta-35 with a working shutter today is a little less likely.

Values

Expect to pay around $300 to $450 for a Minolta Model I, more for the earliest models, and $175 to $250 for a Model II.

- Log in or register to post comments