My 3 Favorite Vintage Cameras: Why Shooting with Analog Classics Is So Much Fun!

I confess to being a cantankerous old coot who cut his photographic eyeteeth deep in the analog era. But I love digital cameras and the amazing things they can do, and I use them exclusively when shooting in color, which comprises about 60% of my work. As for the other 40%, I shoot black and white and I’m a dyed-in-the-wool film guy.

I load my black-and-white emulsions into an impressive assortment of vintage of 35mm SLRs and rangefinder cameras, dozens of medium format marvels ranging from rangefinder folders to SLRs, and I confess, a veritable museum collection of German Japanese, and (yes!) American-made twin lens reflexes.

I love them all, especially my three favorite vintage cameras, which I showcase in this story. Read more about my top three go-to classics and see images I shot with them below.

Vintage Medium Format TLRs and SLRs: Assets & Liabilities

I adore classic 2-1/4 twin-lens reflexes because they pack a lot of picture-taking prowess into compact, well-balanced nicely integrated packages. They all feature folding waist-level viewfinders, which means the viewing/focusing image is laterally reversed and you have to look down into the finder while composing the picture.

This makes it easier to shoot pictures of people on the street without attracting their attention, but it’s not so great for tracking subjects that move across the frame. For that you can use the frame-type sports finder built into their focusing hoods, but then you have to estimate shooting distances.

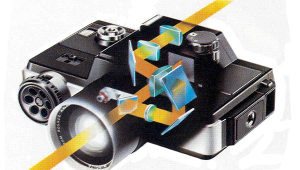

On some models you can achieve right-way-round viewing by detaching the waist-level finder and mounting an eyelevel pentaprism or porroprism finder, but they’re heavy, bulky, often expensive, and the latter decrease viewing brightness.

On the plus side, the TLR’s viewing image remains bright and visible before, during, and after exposure, and the lack of a flipping mirror combined with an inter-lens leaf shutter means you can handhold a typical TLR at 1/30 or even 1/15 sec and still capture crisp images. With a TLR, parallax (the difference between what the viewing lens shows and the taking lens captures) increases as you focus closer and becomes really problematic at distances closer than about five feet.

Rolleiflexes, Rolleicords and a few other TLRs provide automatic parallax compensation over the entire focusing range, using an ingenious moving frame under the focusing screen that shifts vertically as you focus. It works remarkably well but these cameras can only focus down to about three feet. All but the earliest Mamiya TLRs have interchangeable lenses and can focus a lot closer, employing a bellows and a double track rack and pinion focusing mechanism.

The downside: you have to estimate and manually compensate for parallax and recompose the shot using guidelines inscribed on the viewing screen (Mamiya C220) or a “red line” parallax indication system (Mamiya C330).

Analog 2-1/4 square SLRs have the great advantage of providing parallax-free viewing and focusing with any lens, and most of them can focus closer than a typical non-interchangeable-lens TLR like a Rolleiflex or Yashica-Mat. Being able to focus a normal 75mm or 80mm normal lens down to two feet instead of three may not seem like much of a difference but it’s crucial, especially in portraiture and art photography.

Vintage 2-1/4 SLRs also have waist level viewfinders and a great hulking mirror that must flip out of the light path before the shutter fires. That increases shake inducing vibration in handheld shooting, even in models with leaf shutters and non-instant-return mirrors like the Kowa Six and Hasselblad 500C/M.

My favorite Bronica S2A has an instant-return mirror and a large cloth focal-plane shutter, so it fires with a loud “ker-chunk,” and about 20% of the handheld images I shoot at 1/30 sec are afflicted with blur attributable to camera shake (which is why I shoot at least two frames of each shot as insurance!) Logically, an instant-return mirror should not cause any extra camera shake because it returns to viewing position after the exposure has been made, but a large focal-plane shutter definitely causes more vibration than a leaf shutter because of the greater mass of its laterally moving parts. Other advantages of 2-1/4 SLRs: interchangeable film magazines, a greater range of interchangeable lenses, and depth-of-field preview.

1. The Rolleiflex Automat MX EVS of the mid 1950s, a favorite of the great Chicago-based street photographer Vivian Maier, is number one on my list.

Based on the landmark Rolleiflex Automat of 1937, it features fully automatic first frame positioning, effective parallax compensation over the entire focusing range, a single stroke film wind crank with auto frame counting, ergonomic aperture and shutter speed wheels nestled in between the sides of the viewing and taking lenses, and a well placed shutter speed ad aperture window you can see by glancing downward over the erected waist-level focusing hood.

It’s an elegantly compact, masterfully integrated package that can yield images of impressive quality and it’s whisper quiet and virtually vibration free. The coated 75mm Zeiss Tessar or Schneider Xenar lenses are both outstanding—to me the Tessar is “wiry sharp” while the Xenar is “smoothly or less aggressively sharp,” but both can capture superb detail.

Both these lenses are a little soft in the corners and edges of the field at their widest apertures, but otherwise they perform on a par with the vaunted 75mm f/3.5 Zeiss Planar (5- or later 6-element version), said to be the sharpest lens ever fitted to a Rolleiflex TLR.

Rolleiflex downsides: No interchangeable lenses, and focusing to three feet. If you want to get closer, the Rolleinar close-up sets (try the Series 1, +1 first) perform extremely well and provide reasonably effective parallax using a prism built into the viewing lens adapter. Expect to pay $300 on up for a really pristine example.

2. The Mamiya C220: In production from 1968-1981, this classic interchangeable lens TLR was the primary camera used by Diane Arbus, the renowned art photographer.

The Mamiya C220's lenses come in sets of two, each mounted on an interchangeable lens board held in place by a stout steel spring clip. A manually set baffle arrangements lets you switch lenses with film in the camera. Compared to the elegant Rolleflex the Mamiyaflex C220 (a refined, lighter version of the Mamiysflex C/C2 of the ‘50s) comes across as a contraption, but it’s extremely robust and reliable, endearing in its own way, and a superb, very flexible picture taker.

The standard 80mm f/2.8 Mamiya-Sekor lens is a 5-element 3- group Heliar design and its imaging performance is exceptional, even wide open. I prefer the older “chrome” version with the Seikosha MX shutter because the lens has a 9-bladed diaphragm that enhances its beautiful natural bokeh. Later black finished versions with Sekosha S or Seiko shutters have 5-bladed diaphragms like post-WWII Rolleiflexes.

Aside from interchangeable lenses, the greatest advantage of the Mamiya C220 is close focusing (via bellows and a dual rack-and-pinion arrangement). The viewing/focusing image with the standard screen is reasonably bright and crisp, but I’ve installed a Maxwell Hi-Lux screen (for info email maxwellprecisionoptics@yahoo.com), which is far superior in terms of both brightness and contrast. Mamiya C220 downsides: separate film wind and shutter cocking (blank exposure prevention but double exposures possible), manual parallax estimation using lines on screen requires recomposing.

If you want combined film wind and shutter cocking, a real film-wind crank (not a small one hinged into the film wind knob) and moving parallax indicator lines in the finder, go for the Mamiya C330. Mamiya C220s in really nice shape with normal lens fetch $250 and up. Comparable C330s go for about $100-150 more.

3. The Bronica S2A, often called the “Japanese Hasselblad” is a modular 2-1/4 square format SLR released in 1969 by Zenza Bronica of Tokyo.

The renowned award-winning pro Dan Wynn used Bronicas in the ‘60s and ‘70s. The S2A features a cloth focal plane shutter with speeds to 1/1000 sec with X sync at 1/40 sec, has an extensive line of outstanding Nikkor lenses made by Nippon Kogaku (Nikon), interchangeable 120/ 220 film magazines, and interchangeable waist level or eyelevel prism viewfinders. It was the successor to the very similar Bronica S2 of 1965, the major difference being more reliable steel gears in the film advance mechanism and a smaller diameter film advance knob.

S2A models can be identified by an S2A serial number prefix on the body. Later examples produced after 1973 (serial number 150037) lack the S2A prefix and feature improved wingless strap lugs. The S2 is also a reliable camera if you’re not too rough when winding the film, but relatively few camera repair companies will repair Bronicas and they can be expensive to fix (as are all 2-1/4 square SLRs). Bill Moretz at Pro Camera Repair of Charlottesville, Virginia has done a great job repairing a few of mine.

The Bronica S2A is a beautifully made, very attractive camera with a stainless steel chassis and it was made in chrome or black finish. It has a very good viewfinder, its excellent standard 75mm f/2.8 Nikkor lens (a 5-element, 3-group Heliar type) focuses down to about 18 inches and it’s extremely sharp even wide open, falling off ever so slightly in the corners at f/2.8, and has gorgeous bokeh. The multicoated version is marked P.C and the superb, relatively rare, and pricey ($400 and up) 6-element, 4-group double Gauss design version is marked H.C (no dot after the C in either case).

I prefer the Bronica to my Hasselblad 500 C/M because it focuses closer and since I seldom take surreptitious pictures I regard its clattery shutter/mirror mechanism as an endearing quirk. You can snag a pristine example of one of these beauties with the standard 75mm f/2.8 Nikkor P lens for about $350 on up. The later, slightly larger and less elegant Bronica EC, which has an electronically controlled focal-plane shutter and a split mirror is another good choice for Bronica fans at about $450 with normal lens.

- Log in or register to post comments