Adventure Shooter Lucas Gilman Reveals the Tech & Techniques Behind His Extreme Outdoor Photos

All Photos © Lucas Gilman

We were going over the photos for this story when photographer Lucas Gilman said something I didn’t entirely agree with. He was talking about making an image in which a bird came into the frame just as a surfer was making his move on a wave. “Cameras are so good now, anybody can take the exact same pictures I can,” he said, “so what I do is look for and take advantage of subtleties that others overlook. That way I separate myself from everyone else who can buy a new camera and make great pictures.”

I thought that his pictures were great for reasons other than subtleties. The capabilities of cameras, lenses, and lights are vital for capture, and subtleties add the equivalent of grace notes, but for me concept and realization made his adventure and lifestyle images stand out.

A few photos later I got to say so. “This photo—the surfer at the pier—what sets you apart here is the idea, and probably a lot of prep.”

“Yeah, you’re right,” he said. “It took a couple of days to figure out where the light and the waves would be at that time of day, where to put the strobes, and then take the test shots.”

That said, the gear’s got to be as great as his determination, and his technique rock solid.

Need For Speed

Right off the bat you need fast glass and fast shutter speeds. For surfing, kayaking, skiing, and other peak-action moments, Gilman always tries to shoot 1/3000 second or faster with lenses f/2.8 or faster. “And having a 24mm f/1.4 for scenics is very helpful,” he says, “because I’m out to freeze the person in the scene as well as every water droplet.”

His list of must-have lenses starts with the 24-70mm f/2.8 for its versatility; he estimates 80 percent of his images are made with it.

Second is the 80-400mm f/4.5-5.6. “It’s a great combination of reach, especially with a 1.4 teleconverter, and relatively light weight, and it allows me to hand-hold for surfing shots.” The third lens is the 24mm f/1.4. “Fast, sharp, and wide, and a lens for low light.”

The camera these lenses are attached to might be a Nikon D4S or a D750, but is most likely a D810, which, when hand-holding isn’t possible, will be attached to a Gitzo Traveler tripod. “It’s very strong, and I’ll weight it down with a camera bag or a mesh bag filled with rocks to stabilize it. Having that kind of stability to shoot those long exposures is paramount.”

Speed also comes into play with his lighting gear, which he uses from time to time for surfing images. “I’ve put Profoto B1s on beaches and on piers, and will shoot high-speed sync at 1/3000 second or faster to freeze every water droplet and give the photo the drama and crisp sharpness that draws out the action. And I’ll often use a Profoto TeleZoom Reflector to add to the reach of the strobes.”

Working With Athletes

It helps if you’ve done the skiing, kayaking, climbing, and surfing. “The better you know the sport, the better you’ll be able to photograph it,” Gilman says. He allows that knowledge can come from studying the sport as well as participating, but in both cases you need to know what’s perceived as good in that sport.

If you’re a participant, chances are you’ve developed a network of athletes you can photograph. Or, Gilman says, “You can go to an REI, a climbing store, or a surf shop and ask around. ‘Is there anybody really good who works here? Who you can connect me with? Someone who might be looking for pictures?’ Once you’ve proven yourself with pictures, and have a portfolio, you’re able to work with better and better athletes, and the better the athlete, the better the image.”

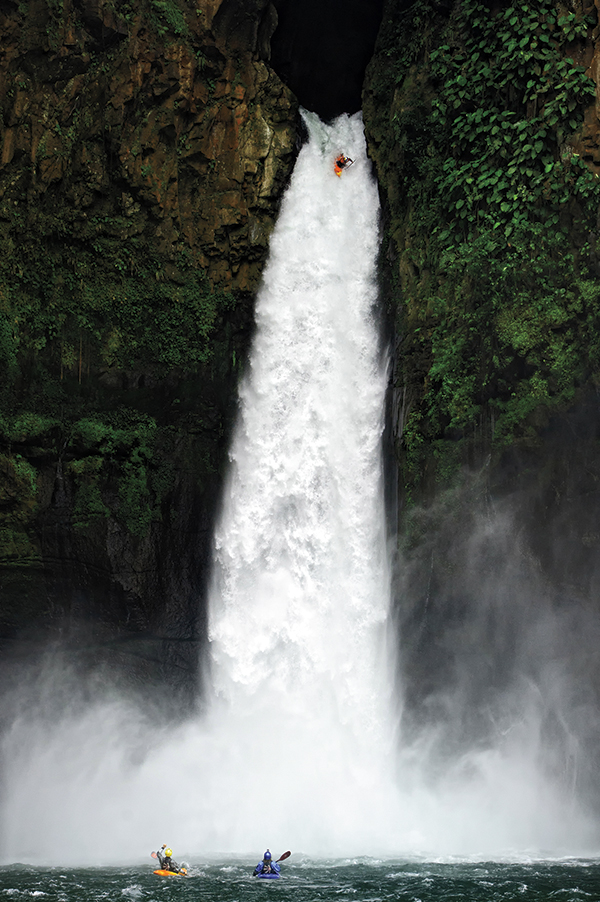

There are two vital points to consider regarding athletes. One is respect and regard. Some actions are repeatable—a surfer is going to keep surfing, a skier pretty much the same—but some things you get only one shot at, like a kayaker running a big waterfall. “Typically they’ll do it only once,” Gilman says. “When they drop an 80-foot waterfall, it’s like a front-end collision with a small car. You can’t be saying, ‘Let’s do another take.’”

Which is why Gilman often sets up remote cameras to maximize the return on one-shot runs. “I’ll sometimes have three cameras set up, at different angles and set for horizontals and verticals. You never want the art director to say, ‘We loved the take, but you didn’t have a vertical so you didn’t get the cover.’”

The second thing about working with athletes is that you can’t lose a card, damage a drive, or not have more than one backup. “If you don’t bring the shots home and deliver pictures to the athletes, they’ll never work with you again.”

So backup is serious business. “Every day on a shoot we download everything to two hard drives,” Gilman says, “and we keep the original cards, but we don’t keep everything in the same place. The assistant might carry the hard drives, and I carry the SD and CF cards, and maybe one of the athletes will have a third piece of data. You don’t leave all your data in the hotel room or in the car; I always want to have geographically separated backups.” And even waterproof ones: “I’ve worked with G-Technology to develop a waterproof hard drive. I don’t want to worry about a drive in a camera bag that gets splashed. You can’t come back to a client and say your drives got wet and you lost some data. That can’t happen.”

It’s Elementary

In adventure photography, there are things you can control: gear, itinerary, and to a certain extent, athletes. Then there’s the big one you can’t: the elements.

“It’s vital to know what the weather will be,” Gilman says, “so we can take advantage of what are often very small windows of light. We all carry smart devices and use everything from the Weather Underground app to area-specific local websites. We check forecasts, storm tracks, radar patterns, everything.”

But you can’t be too tightly controlled by forecasts. “I did a shoot with surfers in Iceland—it’s one of the most magical places on the planet. We’ve had days when we got up at 3:30 in the morning—it’s raining, but we went out. Then it gets colder and it’s snowing. Then the wind’s up and it’s snowing sideways. But one time we had five minutes of light and got one shot against a beautiful, glowing morning sunrise background before it went back to a whiteout. Now, the weather forecast had said snow, but we went out anyway.

“There are going to be days when it’s likely you’re going to get skunked, but you just have to put yourself out there.”

See more of Lucas Gilman’s work on his website, lucasgilman.com. You can view his Instagram posts at instagram.com/lucasgilman.