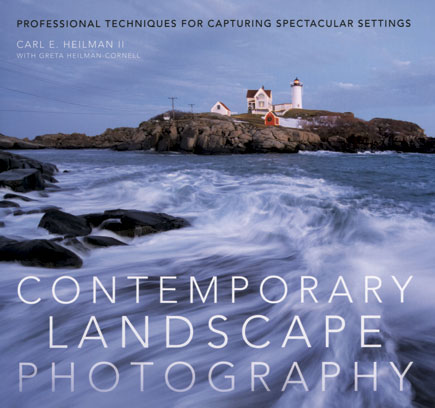

Contemporary Landscape Photography; Carl Heilman’s Complete Course

The following is an excerpt from Contemporary Landscape Photography by Carl Heilman II (Amphoto Books, $24.99, paperback, published June 2010). In his first instructional book, Heilman II shares his experiences and techniques in capturing stunning landscape images. With nearly 300 color photos, this illustrated guide is a complete course in taking pro-caliber images of both urban and natural landscapes.—Editor

Mist & Fog

Working in light mist or foggy conditions can conjure up all kinds of moods for photography, from a heavy, foreboding look, to a mystical, spiritual feel. Fog and mist are simply clouds that are in contact with the ground, and since they are composed of tiny water droplets they take on the hue of the light in the atmosphere. Knowing why fog occurs can help you understand when to expect it—and where.

|

Vaporized moisture is held in suspension between the air molecules in the atmosphere. When the air is warmer, these air molecules are farther apart and can hold a higher percentage of suspended water molecules. As air is chilled—as a result of the temperature cooling overnight, or from the cooling that occurs as it is pushed up over a mountain—the temperature can drop to a point where it can no longer hold all of the water vapor. The excess moisture condenses onto minute particles in the air, creating varying intensities of mist and fog.

Bog |

|

|

|

|

Fog can occur in many different situations, but it’s always because the air is over-saturated by the available moisture. It is quite likely to form on a calm night before a weather system moves in, and on mornings after a relatively calm, warm day is followed by a much cooler night. This is also why mist is found around the base of large waterfalls, over oceans and lakes when the air temperature is well below that of the water, over snow during a warm rain, as well as other situations when relatively warm, moist air is chilled to a temperature that is below its saturation point. Fog is also more likely to form over bodies of water because of the higher moisture content of the air above the water. In winter there is often valley fog the morning before it is going to rain, but not before a snowfall.

Otter Cliff |

|

|

|

|

Determining the camera exposure is one of the biggest issues in foggy conditions, but fog is typically about 1⁄2-11⁄2 stops brighter than the camera’s 18% gray target. As such, the camera’s light meter will tend to underexpose foggy scenes and create muddy, dark images. With multi-segment (matrix or evaluative) metering, start by setting the exposure compensation to +1 to give one stop of overexposure, then check the histogram and shoot again, or bracket.

St. Regis Mountain |

|

|

|

|