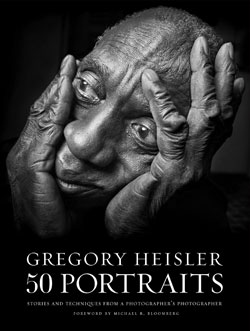

Gregory Heisler: 50 Portraits: Stories And Techniques From A Photographer’s Photographer

Foreword By Mayor Michael Bloomberg

Widely regarded as “a photographer’s photographer,” Gregory Heisler has been described as having “the mind of a scientist, the heart of a journalist, and the eye of an artist.” Known for his candor, humor, and generosity as a teacher, he is able to convey the most complex photographic concepts simply and elegantly. In the long-awaited Gregory Heisler: 50 Portraits (Amphoto Books, October 22, 2013, $40) he takes us on a guided tour of his innovative editorial images and iconic portraits, engagingly illuminated by his insightful and highly personal perspective.

The book draws upon 35 years of richly varied experiences as a portrait photographer working at the highest level for many national and international magazines—including Time, for which he shot more than seventy covers—corporations, advertising agencies, and private clients. Evocative portraits of celebrities and personalities such as Muhammad Ali, Tim Burton, Daniel Boulud, Mick Jagger, Denzel Washington, and Julia Roberts are accompanied by the stories behind the images, providing fascinating context. Readers will learn what Harry Belafonte, Bruce Springsteen, and Yasser Arafat were like during their shoots, why Heisler’s portrait of President George Bush led to his White House clearance being revoked, and what it was like to photograph O.J. Simpson after his acquittal.

By offering a fascinating, plainspoken exploration into his creative process, Heisler generously shares exactly how he made the images, but more importantly, he explains the “why”—the rationale behind his creative choices, working methods, and strategies. Further, he offers insights into his favorite tools, ranging from vintage cameras to the latest lights, and explains why he used them to create specific images. Heisler is such a gifted storyteller, that for anyone with even a passing interest in photography, it’s a fascinating look at the types of choices a photographer has to make, and how arresting images get made.—Liner notes supplied by the publisher.

I have admired Heisler’s work, his acumen and demeanor, for many years, and was thrilled to see this impressive volume of his work. But while the images are filled with the fidelity of the personalities portrayed, what also impressed me greatly in this book was his conversation about the images, the people he photographed and most of all the way he sees, manifests, and works to attain his vision. The book reads like a photographer talking to photographers, but also informs those who might never have picked up a camera how a photographer thinks and why images have meaning beyond their surface appearance. Great images, great read.—Editor

Muhammad Ali

Ali had already been a generous host at his old farmhouse in Berrien Springs, Michigan, treating us to magic tricks and joking with us (at one point he quietly leaned his massive frame against a bathroom door, preventing the photo editor from emerging). We had just finished shooting the portrait that would ultimately run on the April 25, 1988, cover of

Sports Illustrated.

Earlier, though, he had sat silently on his sofa, seemingly in a stupor as he watched a television show while we set up our cameras. It was as if he crackled in and out of clarity like an old radio. Here was The Champ, the biggest and most gregarious figure of his era. He didn’t appear unwell or unhappy, though; if anything he seemed at peace inside his own head, isolated from the world by his trauma-induced Parkinson’s. It was that quiet, peaceful but powerful aloneness I wanted to somehow see in the portrait I had yet to make.

Sometimes the best you can do is to be a spectator to your own creative process as it winds itself out and wraps around an idea, a feeling. I remember walking farther and farther from the house just to get some space. We were frozen. My assistant, Howard Simmons, had been standing in the snow for a long time as we finessed the light. And I remember photographing Howard tight and loose, high and low, trying to find the right vantage point and framing. Mostly I remember waiting many long freezing minutes for Ali to make his way from his house to our little spot, moving incrementally in a painfully slow shuffle through the snow.

When he finally arrived, stone-cold and expressionless, he looked silently at me as I explained: there would be a tiny little spotlight shining on him; if he moved, he’d be lost to the light, so he would need to stand stock still. I couldn’t tell if he heard me; he betrayed nothing. I climbed up to the camera on its tall tripod and exposed a few rolls of film. As I watched him squinting over the snow, I thought I could see his lips begin to move. I hopped down into the snow, made my way over to him, and leaned in close. In a hoarse whisper, he was saying, “You’re crazy, man. You’re crazy.” He looked right at me and smiled. “But you love what you do, don’t you?” And with that, he abruptly wheeled around and took off at a trot for the fireplace warmth of his farmhouse.

Thoughts On Technique

It’s not moonlight.

This picture was actually made in the hazy sunlight of a late afternoon. It’s not digitally manipulated. The technique that creates this effect is only available to still photographers because it combines flash (or strobe) illumination with daylight.

An electronic strobe emits a momentary burst of light: literally, a flash. So no matter what shutter speed your camera is set at, the strobe doesn’t care; it spits out its flash of light and is done. The flash intensity or brightness is measured in f-stops. If a flash puts out f/8, then it’s the same bucket of f/8 light at 1 second of exposure as it is at 1/250 sec.; the f/8 component doesn’t change. It’s just a flash. So when you want to control the brightness of your f/8 flash, you use your aperture.

If you set it at f/11, then the flash will appear darker; at f/5.6 it will look lighter. So your f-stop camera control is like a rheostat for your flash exposure. Again, the shutter speed has no effect, because the flash is just an instantaneous burst

of light.

The shutter speed, then, becomes a rheostat for the ambient light, independent of the flash. They are two completely separate variables. So if I have f/8 strobe light falling on my subject, the background can be at any of a wide range of shutter speeds without affecting it. If it’s a sunset, f/8 for 1/60 sec. might make the sky look airy and bright, while an exposure of f/8 for 1/250 sec. might render it deep and rich. But my subject, lit by only the flash, gets f/8 either way and is unchanged. So, again, the shutter speed acts like a rheostat for the background, while the aperture is like a rheostat for the flash. This is powerful stuff.

For this image of Ali, my little spotlight flash is illuminating him with f/16 of strobe light. So I set my f-stop at f/16. When my shutter speed was 1/30 sec., the sky and the snow were pure white; not very dramatic. When my shutter speed was 1/125 sec., they became a light gray tone. Now it starts to get interesting. Finally, when I changed my shutter speed to 1/500 sec., the snow and sky darkened to a charcoal gray. Moonlight.

Danny DeVito

The camera was on the floor. I was on the floor. The chair was a child’s chair. Danny DeVito loomed large, filling the frame. I was shooting him for a profile for the New York Times Magazine that focused not on his comedic career as a diminutive, irascible caricature but on his new career as a formidable film director.

It was early morning in a rented storefront studio in Los Angeles. The assistants and I were drinking coffee and figuring out our day. I had decided not to shoot DeVito on a plain paper background, fabric backdrop, or cyclorama wall. I wanted him to be someplace. So I chose to use the studio as a real location, as if we were in his home or production office. I looked around the place; there wasn’t a whole lot to work with. All the seating options would only make him look that much smaller: director’s chair, a large leather sofa, and a tall makeup stool. (The director’s chair wouldn’t be an option anyway; in his case it would have been too much of a cliché.) There was no stylist and nobody available to go prop shopping, so I went. I didn’t mind; when I’m out looking around, I often stumble upon something that I’d never have considered or known to ask for. Plus, it gives me some time on my own to mull over the day’s possibilities.

I hit some of the vintage furniture shops nearby on LaBrea. There were some terrific pieces, but they were too good; they’d draw attention away from my subject rather than focus the viewer’s attention on him. Then I spotted it: a two-tone reproduction art-deco club chair. A child’s club chair. Half-size but not kiddie-cute; it looked like a sophisticated piece of furniture, just smaller. So I negotiated a rental fee, threw it in the car, and ran it back to the studio.

When DeVito showed up, he saw the chair sitting all alone in the studio, surrounded by lights; it was obvious this was to be his little throne for the afternoon. But he got it. He saw that it wasn’t a cartoon. He is, in his own way, a big man: stocky, barrel-chested, thick. He more than filled the chair. When he sat straight-on, he hid it. So I spun the chair sideways and tried a Hitchcockian profile. Too corny. He rolled on his hip, flung his arm over the back of the chair, and turned to face me. Now the picture was dynamic, all angles. His shoulders were a counterpoint to the blinds in the background. His black suit offered an imposing silhouette, particularly from my low angle. He swiveled his famous head, gazed down at the camera, and gave me the look.

Thoughts On Technique

Broad lighting. Short lighting. Rembrandt. Butterfly. Clamshell. These are all terms used to describe various lighting schemes for portraiture. Unfortunately, some, like broad lighting, are discouraged, while others, like Rembrandt lighting, are often preferred. I’m an equal-opportunity illuminator. I’ll use whatever works.

Broad light is when all the real estate on the broad, or near, side of the face turned toward the camera is illuminated, nose to ear. Short lighting, on the other hand, is when the light falls on the narrow, or short, side of the face turned away from the camera. In short lighting, the subject’s nose is pointed toward the light.

This is thought to be more pleasing, slimming, and flattering. In broad lighting, the subject’s nose is pointed away from the light, which is thought to result in a less favorable portrayal, because it tends to broaden the face and make it look heavier.

But there are really no set rules about this sort of thing. It’s always a judgment call. Painters for centuries have used broad lighting to create portraits with great character. (The work of John Singer Sargent comes to mind.) Yet it’s always Rembrandt whose praises are sung in the lighting department. It’s really not fair.

Seminal portrait photographers like Irving Penn and Arnold Newman often used broad light to great effect. In this portrait, flattery wasn’t the top priority. I didn’t want him to not look good, but it seemed more important to get past the familiar funnyman, to evoke a sense of the auteur—a side of DeVito that his public hadn’t seen, a potentially darker side, certainly more serious than what they were used to.

One characteristic of broad lighting is that it throws the front plane of the face into partial shadow, creating a sense of the not quite known. Combine it with a turn of the head and the subject can look wary. Things are left unseen, which can be a bit disconcerting in a portrait. There’s nothing wrong with disconcerting; in fact, sometimes it can be just the ticket.

About The Author

Gregory Heisler is a photographer and educator renowned for his technical mastery and thoughtful responsiveness. His iconic portraits and innovative visual essays of celebrities, world leaders, and sports stars have graced the covers and pages of Life, Esquire, GQ, Sports Illustrated, ESPN, and The New York Times Magazine, though he is perhaps best known for his more than seventy cover portraits for Time magazine. Among the honors he has received are the Alfred Eisenstaedt Award and the Leica Medal of Excellence. A sought-after speaker and educator, he has taught at the International Center of Photography, the School of Visual Arts, the Smithsonian Institution, the National Geographic Society, scores of workshops and seminars throughout the country, and is currently Artist-in-Residence at the Hallmark Institute of Photography. He can be found online at www.gregoryheisler.com.

Where To Buy

Gregory Heisler: 50 Portraits: Stories and Techniques from a Photographer’s Photographer (ISBN: 9780823085651, $40) is available wherever books are sold.