Tamron SP 35mm f1.8 Di VC USD and SP 45mm f1.8 Di VC USD Lens Review

To make a better lens, one that avid photographers might even be inclined to leave on their DSLR camera permanently, Tamron set aside all of their former notions about lens design and construction and went straight back to the basics with the new Tamron SP 35mm f1.8 Di VC USD (Model F012) and SP 45mm f1.8 Di VC USD (Model F013) prime lenses, which are the subjects of this review.

Recognizing the importance of keeping pace with the growing trend of higher and higher density image sensors, Tamron concluded that an all-new approach was necessary with the SP 35mm f1.8 Di VC and the SP 45mm f1.8 Di VC. Taking advantage of the expertise and technical knowhow they’d accumulated in nearly six decades of building lenses for cameras and other precision devices, Tamron set out to recast their legendary SP (Superior Performance) line of lenses.

These first two models are prime lenses that embody a new, more rigid performance standard and a fresh new exterior design. They are suitable for both full-frame and APS-C (cropped-frame) DSLRs.

Price

I never lead with price in a review, but in this case the price is a big part of the story. The most surprising part, for certain. When Tamron first unveiled these two lenses to a group of journalists in New York on September 1, the announcement of the price electrified the audience.

Actually, the number was initially whispered to a few people clustered around the display table and quickly spread throughout the room. Based on other lenses currently in the marketplace, I would have guessed that these lenses would be priced at least $100 or even $200 higher than the official $599 price tag.

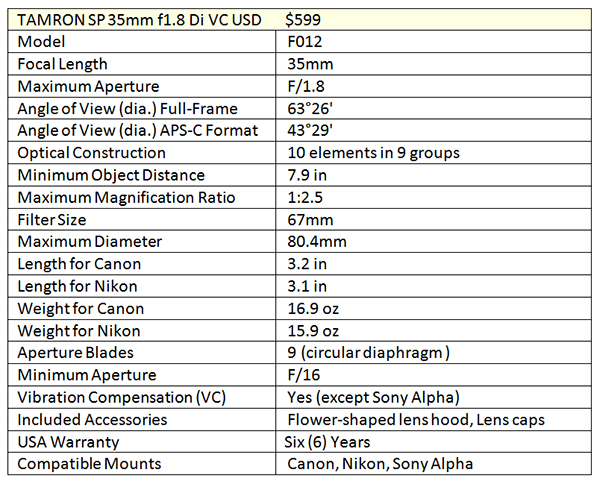

The Tamron SP 35mm f1.8 Di VC USD (Model F012) and SP 45mm f1.8 Di VC USD (Model F013) are available in Canon, Nikon, and Sony mounts (though the Sony version doesn't have VC because image stabilization is built into Sony's interchangeable lens cameras).

Prime vs. Zoom

Both the 35mm f1.8 and 45mm f1.8 lenses are prime lenses. Advanced amateurs know the difference, but for beginners a prime lens is quite simply a lens that is not a zoom. That’s the distinction by definition.

In terms of performance, it was once safe to say that high quality prime lenses always outperform high quality zooms within similar ranges. But the line between them has become blurred in recent years.

Tamron makes three other primes, all Macro lenses. They are the 60mm f2.0, 90mm f2.8 VC and the 180mm f3.5. The latter two are for full-frame DSLRs. All three are excellent performers; my favorite is the under-appreciated 90mm f2.8 VC which is perfect for portraits in addition to life-size, 1:1 Macro work.

What is a “Standard” Lens?

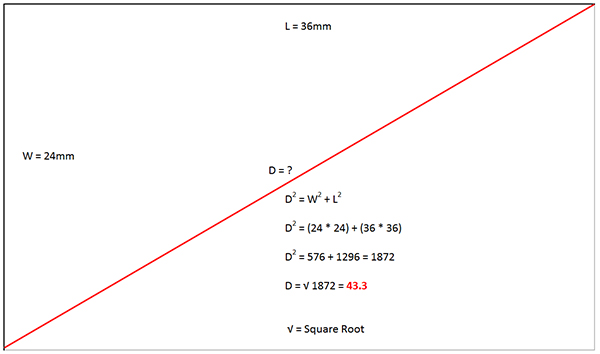

The “standard” or “normal” focal length for any camera is determined by the diagonal of the image sensor. Cameras with full-size sensors (i.e., CMOS or CCD sensors the same size as a single frame of 35mm film which is 24mm x 36mm) therefore have a “normal” focal length of about 43.3mm. It’s geometry, specifically the Pythagorean Theorem.

A normal (standard) lens sees the world with approximately the same perspective as human eyes. Field-of-view is vastly different, because binocular humans have peripheral vision that extends nearly 180 degrees (although our brain often ignores the far edges). But the relative object sizes and perspective are very close to a match.

The Tamron 45mm f1.8 is as close as you can get to the mathematically prescribed normal focal length that we call standard. On a full-frame DSLR, it offers an everyday, all-day lens that’s great for street shooting, general photography, nominal close-ups and just about everything.

The 35mm f1.8 is wider than normal, but still a focal length highly prized by photojournalists and street shooters. The slight wide-angle delivers more depth-of-field at every f/stop.

Both lenses feature category-leading close focus (minimum object distance) capability. The 35mm focuses to 7.9-inches and the 45mm to 11.4-inches.

Magnification ratios are 1:2.5 and 1:3.4 respectively. Magnification ratio simply explained: if an object 2.5-inches long is captured as an image 1-inch long, the magnification ratio is 1:2.5. By convention, true “Macro” begins at a ratio of 1:1, sometimes called “life size.” So as far as this spec is concerned, 1:2.5 is better than 1:5, for example.

Human Touch

Ergonomics is a word that went from fresh to overused in just a couple of decades. One of Tamron’s goals was to create a lens style that’s comfortable to use and a delight to own. This new line is distinguished by a soft-gold tone ring positioned just above the metal lens mount.

Fast F/1.8 Aperture with Circular Diaphragm

Both new Tamron primes have apertures of f/1.8. There are three distinct advantages to having a large aperture. The most obvious is the ability to shoot in low light at a reasonable shutter speed. In the case of these (and many other) Tamron lenses, the VC image stabilization compounds this ability to enable the user to take a whack at the proverbial black cat in a coal bin.

The second, less obvious, advantage is that large apertures deliver more light to the DSLR viewfinder thereby facilitating focusing.

Finally, large maximum apertures give the shooter more control over depth-of-field and allow creative use of selective focus. This, of course, leads nicely into the subject of bokeh.

Bokeh

One of the most misused terms in photography, bokeh is a Japanese word that literally means unsharp. It’s generally applied to the area of a photograph that is out-of-focus but can also be used to describe people who spend too much time worrying about such things.

Aside from the questionable virtue of providing pretty patterns of fuzzy shapes, the real benefit that comes from “good” bokeh is that the unsharp areas make the sharp parts of a photograph look even sharper.

The Tamron 35mm and 45mm lenses do deliver attractive bokeh. That’s a subjective valuation, but there is science behind it.

The large f/1.8 aperture can be leveraged to produce minimal depth-of-field, thereby isolating the main subject and separating it from the background, as commonly seen in portrait photography. In addition, both lenses have circular diaphragms. That means point sources of light in the background will mostly make circles instead of multisided equilateral polygons.

VC Vibration Compensation

Unsharpness created by camera movement is the number one cause of unpleasant photos. Image stabilization is becoming so commonplace that you have to wonder why no one besides Tamron is applying it to standard lenses. While it’s true that camera jitters are more pronounced with telephoto lenses, “the shakes” exist at all focal lengths.

Both the 45mm and 35mm Tamron primes feature VC, Tamron’s proprietary Vibration Compensation stabilization system. It’s very effective and particularly helpful when shooting in dim light and close-ups.

With a normal lens that’s an f/1.8 you often find yourself shooting indoors without flash at shutter speeds of 1/25 second or lower. While that can be a challenge without stabilization, it’s child’s play with VC.

Technology

Close Focus Floating System

Tamron uses what they call a Floating System that essentially modifies the optical formula on the fly. Lens elements are shifted to optimize sharpness at close shooting distances. Since many conventional lenses are more-or-less a compromise that’s biased toward either near or far objects, moving the individual elements and groups is a brilliant solution.

Both lenses are highly corrected and include molded glass aspherical elements and LD (Low Dispersion) glass. The 35mm combines one LD with an XLD (Extra Low Dispersion) element. Lenses are ground into shape by rotating them on a specific axis. The laws of physics dictate that if something is shaped by rotation, the resultant contour is spherical.

To better understand, imagine a lump of clay spinning on a potter’s wheel. Now imagine trying to make something that’s not rounded or spherical on a potter’s wheel. It can’t be done. Tamron produces aspherical elements by molding them.

Fluorine Coating

Fluorine is a chemical that’s found in super-slick Teflon and serves as the basis for waterproof Gore-Tex clothing and shoe material. Tamron applies a protective Fluorine coating on top of the BBAR and eBand anti-reflective coatings on both the 35mm and 45mm lenses.

The multiple coating layers enhance light transmission and dampen internal reflections. The Fluorine coating sheds water and repels grim and fingerprints.

Moisture Resistance

Sealing out moisture means that dust and airborne contaminants are sealed out as well. So if you’re like me and never intend to use your equipment in the rain, moisture resistance is still an important asset.

Silkypix

Purchasers of select Tamron lenses, including these two, receive a license key and instructions for installing a customized version of Silkypix Developer Studio, a widely popular RAW image converter and editor. In addition to the usual adjustment capabilities, the software helps you harvest every ounce of quality based on the optical data pertinent to the specific Tamron lens.

Made in Japan

Few photo products are still made in Japan these days. Moving fabrication to China and other parts of Asia has allowed manufacturers to keep prices lower and the quality has not suffered.

Nonetheless, if you’ve flown internationally recently you may have seen the “Made in Japan” electronics sections in Duty Free shops. True or not, there is a perception that products made in Japan are of a higher quality. Both the 35mm and 45mm Tamron primes are made in Japan.

Regardless where they’re made, it’s clear that they were conceived and designed with the greatest attention to even the smallest details. For example, the lettering on the lens barrels and lens caps is written in a font that Tamron created from scratch. They did this to assure maximum readability and emphasize ease-of-use.

Field Test: Performance

Cosmetics and Handling

In the hand, either lens provides positive tactile feedback. The build quality is excellent. AF and VC switches are appropriately sized and clearly labeled. The focusing ring is knurled with thin parallel lines that provide sufficient grip. The focus distance window is large and easy to read. I primarily used the 35mm on a Nikon D800 and the slightly longer 45mm on a Nikon D2X. In both cases, the balance was comfortable and encouraged secure, stable shooting.

Autofocus Accuracy and Speed

Both lenses use Tamron’s USD (Ultra Sonic Drive) for fast and quiet autofocus, and both perform flawlessly. At infinity as well as at close-up distances, the focus is quick and sure.

Because of the fast aperture and potential for shallow depth-of-field (always a double-edged sword) I found it better in some instances to shoot in Aperture Priority stopped down to f/5.6 or so. That said, shooting in program was satisfactory as long as I paid attention.

Full-Frame vs. Crop-Frame

On my full-frame Nikon D800 the results were as Tamron imagined—outstanding across the board. Crop-frame sensor cameras use only the center part of the lens (the lens transmits a circle of light large enough to cover a full frame, but the sensor is smaller and therefore uses only the sweet spot in the middle). For this reason, many lenses appear sharper on crop-frames than on full-frames.

In subjective, nonscientific tests I did not find this to be the case. In other words, the lenses are so good even on full-frame sensor cameras that it’s unlikely you’ll notice any difference in performance on an APS-C camera.

The effective focal length changes, of course. On a crop-frame the 35mm becomes the equivalent of 54mm, and the 45mm equates to a 70mm. Although a trifle too short for purists to call a portrait focal length, I found 70mm to deliver satisfying perspective with just minimal compression. (Compression, in this sense, is a function of focal length and physics, not lens quality.)

Edge-to-Edge Brightness

Standing up to critical testing, images were evenly lit edge-to-edge without the vignetting (darkened corners) often associated with wideangles lenses. The large aperture also made it easier to frame and compose under dim conditions.

Color Rendition

Cameras are tuned to favor certain colors unless you shoot Raw. Nonetheless it’s possible to make objective comparative analysis of color fidelity and accuracy. Compared to other lenses I own, I did not find any particular color bias; in other words, I characterize both lenses as neutral as opposed to overly warm or unduly cool. If pressed for either, I’d say they lean only slightly toward warm tonal rendition, which is ideal for portraits (at least on this planet).

The only aberration I could detect was slight purple fringing when shooting a thin or shiny object against a bright backlight. These are the worst conditions for any lens, and moderate purple fringing did appear.

I’m not prepared to identify this as chromatic aberration because DPF (dreaded purple fringe) can be caused by other factors. Except when intentionally invoked, I could not detect any noticeable DPF anywhere else.

Sharpness

Sharpness, particularly edge-to-edge sharpness, is outstanding. The lenses out-resolve the 36.3-megapixel sensor that’s in my Nikon D800.

When viewed at the pixel level, the image quality withstands close scrutiny. Sharpness in the real, non-pixel-peeping world is derived from more than merely lens quality. Image stabilization, in this case Tamron’s VC, counteracts sharpness-robbing camera shake, thereby improving the image overall.

Similarly, isolating the main subject via depth-of-field manipulation also enhances apparent sharpness if done correctly. By every measure, these lenses deliver excellent acutance (edge contrast).

Conclusion

Tamron has created a pair of primes that promise preeminent performance. And they’re popularly priced. They are fast, sharp and very well made. At $599 it becomes just a question of which to buy—or whether to buy both.

—Jon Sienkiewicz