Jeff Gusky Uncovers the Hidden Lives of Soldiers in Stunning Photos of WWI’s Underground Cities

Since 2011, photographer and physician Jeff Gusky has been rooting around ancient rock quarries in France on a mission to document a vast labyrinth of underground cities from World War I. The hidden cities lay beneath former WWI trenches, where tens of thousands of soldiers went about their daily lives under the French countryside as the Great War raged above them.

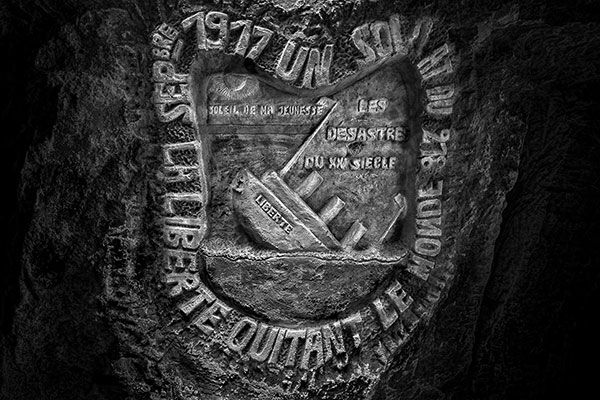

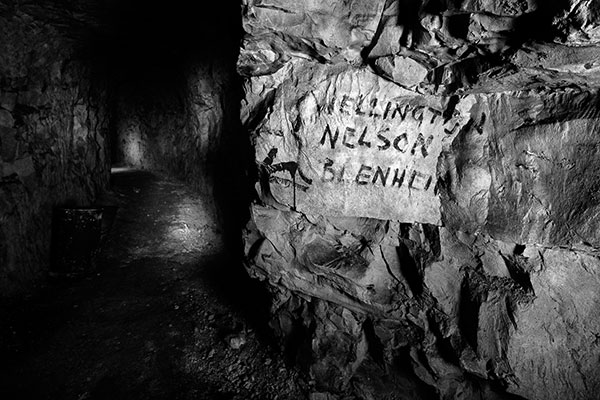

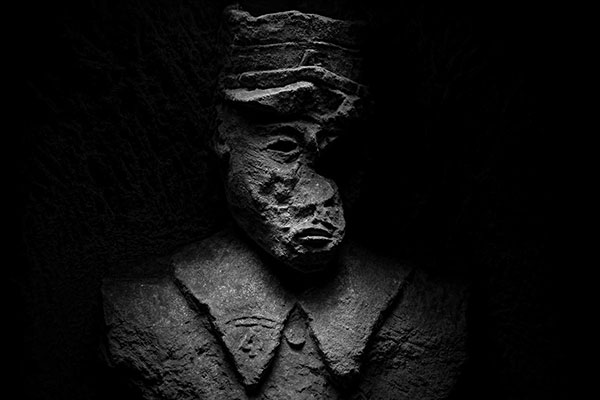

According to Gusky, the hidden cities were surprisingly modern with rail, telephones, electric lights, hospitals, chapels, theaters, offices and even street signs. And much of these subterranean locations have remained surprisingly intact. As his striking, black-and-white photos reveal, walls and crevices are still lined with beautiful art created by the soldiers, including carvings, statues, drawings, and graffiti. In some cases, Gusky has documented WWI-era household items, bottles, canteens, coins, newspapers, gas masks, and bits of clothing, including uniforms.

To get to these cities, Gusky had to first earn the trust of area residents, since most of these locations are on private land in France. But once he got approval, he has returned with his camera again and again to the carved “stairways to hell” that connect the former trenches to the underground cities below.

We recently interviewed Gusky about the project, which is titled “The Hidden World of World War I.” You can see more of his work on his website.

Shutterbug: How did you get the idea for this project?

Jeff Gusky: In early 2011, I was in France on a scouting trip for a documentary with a short segment on the Great War, and realized that France had many remnants of WWI. Later that year, I had a chance meeting with a French government official who was in charge of planning the 100-year anniversary of WWI for France. He graciously introduced me to local officials all along the Western Front who in turn introduced me to local residents. Over time, I earned their trust and they shared their secrets about many, many hidden remnants of WWI, both above and below ground.

SB: What was the biggest challenge of photographing these underground cities?

JG: The darkness! Once I became comfortable working underground in total darkness, it was like being a thousand meters below the surface of the ocean…immersed in a place never seen before by the outside world. It’s a great privilege to bring these hidden places to light through my photographs.

But it was more than just darkness. At times one must crawl through small holes in the ground or climb over jagged rocks where there’s been a rock collapse. In some underground cities, the ceilings are unstable and there was a danger of being crushed. Live ammunition – grenades, bombs and bullets - are often lying about.

SB: What did you discover during your photo explorations of these areas that you completely were not expecting?

JG: In the beginning, I had no clue about how much is still left from WWI. I found vast underground cities loaded with carvings, art and artifacts that looked as if one hundred years ago was yesterday – tobacco pouches, cigar boxes, parts of uniforms, pots and pans, a soldier’s clock, a telephone, newspapers, gas masks, bottles, coins, tools, dishes, cups, china and eating utensils.

Also, thousands of hand-written soldiers’ inscriptions remain on rock walls of underground cities. One can imagine that these men, who were facing the uncertainty of death at any moment, were writing messages to the future in essence declaring: “I was here. I once existed. I was a living, breathing human being.” Soldiers often recorded their names, hometowns, serial numbers and street addresses. It’s part of human nature. We all want to feel like our lives mattered and that someone will remember us after we’re gone.

SB: Can you give us some technical information on how these images were captured. i.e. what type of camera gear did you use, what lighting (if any) etc.?

JG: I carried the equivalent of a portrait studio underground! I shoot with a Canon EOS-1D X with Canon and Zeiss glass, Really Right Stuff Carbon fiber tripod, an Arca Swiss Cube, Canon Speedlites, soft boxes, gobos, grids, beauty dishes, and snoots.

SB: Why do you like black-and-white photography and why do you think this story was best told in black-and-white?

JG: Except for my recent assignment with The New York Times, I only work in black and white. I photograph from my gut. For me, black-and-white photography better communicates emotion and has a certain timeless quality. My photography strives to reveal how the past haunts the present. Black and white communicates this best.

SB: What are you working on next?

JG: We are only five months into the nearly five-year-long commemoration of the 100-year anniversary of WWI, and there’s still much photography left to do. WWI was fought in faraway places like Siberia, China, Africa, The Holy Land and Turkey. Eventually, I’d like to explore and photograph all these places.

We’re now negotiating a television series and other media projects. Also, I’ll soon be delivering keynote addresses and speaking on college campuses.

- Log in or register to post comments