The Stunning Environmental Portraiture of Gregory Heisler

(Editor’s Note: Exploring Light is a monthly Shutterbug column featuring tips, tricks, and photo advice from professional photographers in Canon’s Explorer’s of Light education program. This month's column is by Gregory Heisler on his approach to creating an environmental portrait. Greg is a founding member of the Explorers program and now a member of Canon Legends.)

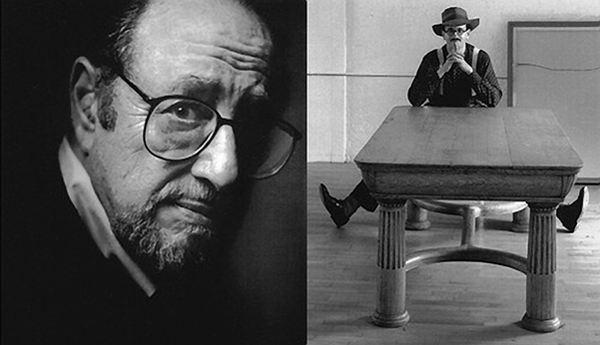

I apprenticed for the man who literally invented the environmental portrait: the legendary photographer Arnold Newman. Since the beginning, photographers had taken pictures of people in environments, but Arnold’s intention was different: he elevated environment to context to create an utterly new kind of portrait.

Arnold Newman envisioned a narrative portrait that would use context to convey his sense of the person. He actually bristled at the term “environmental portrait” because he felt some were more “psychological” or “symbolic” portraits (and he just didn’t like labels). In particular, he often said that his most famous portrait—composer Igor Stravinsky seated at a grand piano, its open lid looking like a giant quarter note —is not environmental but symbolic.

Arnold didn’t take pictures, he made them. It was a process, fully envisioned in his mind’s eye, often quickly and on the spot, yet they were always intentional; they told a story, evoked a feeling. In the 80 or so years since Arnold Newman made his first one, nobody has done it better.

I learned important lessons during my brief but intense tenure with Arnold, all by the example he set: passion for the picture, curiosity about people, hard work and a high bar. And conceptually, it was crystal clear that the relationship between person and place is the defining element in an environmental portrait.

Step One:

I try to learn what I can about the person I’m photographing. Typically, there is little time between receiving the assignment and the portrait session itself; rarely more than a week, sometimes literally the same day. Many of my subjects are celebrities, politicians, actors, sports figures, and people in the news, so it’s likely I’m already familiar with them. If the magazine has the story in hand, I’ll want to read it to think about how the words and images might best work together.

If my subject has written a book, I’ll read it (if time allows); if he or she has acted in a film, I’ll see it; if there’s a performance to hear, I’ll listen to it. Sometimes I’ll read other profiles that have been written about them. Sometimes I’ll try to find a recent photo online just to confirm how they currently look. If I don’t know them, then I’m starting from scratch. Glasses or not? Hairy or bald? Thick or thin?

I then determine where the picture will be made. What time of day? Indoors or out? What are the lighting conditions? Occasionally it’s possible to scout the location in advance, but more often than not I’m actually seeing it for the first time when I arrive to take the picture. So, while I try to have a pretty solid sense of what I’m after, I try not to get locked into a visual idea that may not pan out when I get there. It’s more a jumping-off point.

So, the actual photography process begins with Step One: I arrive on location and first look for my camera position, or P.O.V. (point of view). Do I want to see everything in the picture, or just a slice, a telling fragment or detail?

Step Two:

I find my frame. Location portraiture is very much a matter of wrangling chaos. In the studio you start with a blank canvas in an empty box and build from there. On location, you’re both editor and curator. This stays in the frame, that does not.

Step Three:

I try to envision how I want my subject to appear in the frame. Close or far? Full-length, waist-up, or tighter? Where in the composition? Is the environment dominant, or more of a backdrop? How selective is my focus? Do I want to see every detail, or just convey a sense of the place? Am I suggesting a relationship between my subject and the context, or am I spelling it out? There are no rights and wrongs, just choices to consider.

Step Four:

I figure out the light. This technical consideration can only be addressed after I’ve determined where I’m shooting, what my frame is, where my subject will be, and how much of them I’ll be seeing. There are a million ways to work with light ranging from just working with available light, to completely lighting the scene from scratch. Again, no best way, no worst way, just possible options, with different outcomes.

Step Five:

My subject, the person! Now that I’ve attended to all that other stuff, I can really focus all my attention on the human being in front of my lens. Early in my career I was so preoccupied with everything else, it was like the operation was a success, but the patient died! It was heartbreaking. I had worked so hard on creating the visual— the frame, the light, how it all looked—that I forgot to connect with my person. People relate to pictures emotionally. Always. That’s what they’ll remember: The picture that made them feel something.

This sequence can happen over a longer period or it can literally happen in seconds, making the cascading series of choices very quickly and almost intuitively. Once my intention is clear, the rest just seems to flow.

Bio

Having switched hats from being “a photographer who teaches to a teacher who photographs,” Gregory Heisler is currently the Distinguished Professor of Photography at the Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University. He is perhaps best known for more than 70 cover portraits for Time, as well as his covers and essays for Life, Esquire, GQ, Sports Illustrated, ESPN, and The New York Times. His book, Gregory Heisler: 50 Portraits is now in its third printing. Among the kudos he has received are the Alfred Eisenstadt Award and the Leica Medal of Excellence. Gregory has been profiled in American Photo, Communication Arts, Esquire, Life, and numerous industry periodicals.

See more of Heisler’s work at the links below: