Henry Hamilton Bennett; Legendary Landscape Photographer (1843-1908) Page 2

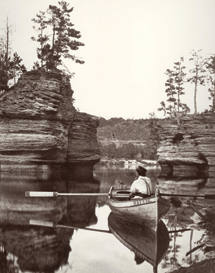

In 1863, naturalist John Muir visited this area. He was captivated by the

"glorious tangled valleys and lofty perpendicular rocks," saying

that "we cannot remove such places to our homes, but they cut themselves

into our memories and remain pictured in us forever." Like Muir, Henry

was enchanted by this rugged wilderness, which became the backdrop for his spectacular

landscape images that made time stand still. The Dells became his photographic

canvas for the rest of his life.

Undaunted by the physical challenge, Henry hauled around colossal cameras, a

portable darkroom, delicate wet-glass plates, chemicals, and water, across the

harsh terrain photographing the lofty sandstone bluffs and narrow, dark ravines,

which required long exposures. He often made two exposures, one with a full

plate and the other with his stereographic camera. Soon he had thousands of

views of the Dells, which he marketed nationwide through sales agents.

Henry made all his own equipment. Excluding the lens, which he purchased, his

carpentry training proved very useful, enabling him to craft extremely fine

precision cameras designed specifically for his needs. Stereo photography was

now at its height and he built his earliest cameras using cigar boxes fitted

with two lenses. He also constructed a camera with a tilting back for perspective

control, and in 1871, before the advent of electricity, he built a solar camera

specifically to make enlargements from negatives using sunlight.

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

An Appetite For Images

By the 1870s, Americans had an insatiable appetite to see the newly explored

wilderness, and stereoscopic landscape photography brought these frontiers vividly

into their living rooms. These were made by two identical frames taken a few

inches apart, then mounted side by side on cardboard and, when viewed through

a stereoscope, they created a three-dimensional effect. The impact and realism

of Henry's stereo images of the haunting rock sculptures of the Wisconsin

Dells fed the public's craving for dramatic landscapes, equal to any they

had seen. Tourism to the Dells began.

Orders poured in and Henry's studio turned out over 20,000 prints per

month. To speed up production of his stereographs, he designed a foot-operated

machine that automatically die-cut, reversed, and mounted his prints in a one-step

process, enabling him to produce several hundred prints a day. Henry never imagined

the impact his photographs would have in attracting tourists to the Wisconsin

Dells, including famous people, like General Ulysses S. Grant and Mrs. Abraham

Lincoln, referred to as the "lady in black" by the local press.

Henry was now nationally recognized as one of the leading photographers in the

country. William Metcalf, a wealthy resident of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and a

personal friend of Oliver Wendell Holmes, was also an enthusiastic amateur photographer

and admired Henry's photographic skills. He became Henry's mentor

and the two became lifelong friends. Metcalf provided financing for Henry to

construct a new studio building in 1875, and after many financially difficult

years, Henry and Frankie finally felt that life had taken a turn for the better.

This new location at 215 Broadway gave a significant boost to Henry's

career. An elegantly decorated sales room where customers were received led

to the spacious "operating room," or portrait studio, where a large

skylight provided diffused lighting. A darkroom and a workroom, outfitted with

a small press for imprinting titles, and the "Bennett Studio" name

on all his photographs rounded off this efficient and profitable business. To

complete his impressive setup was a unique solar printing room, constructed

on a raised circular platform behind the main studio. Positioned on circular

tracks, this room, with a row of windows along one side, could be rotated to

face the sun all day for making prints.

Frankie, who had been sick for sometime, died on August 28, 1884, at the age

of 36. Depressed and overcome with loneliness, Henry found solace in his work.

He built an 18x22" camera and a heavy wooden tripod to support it. Used

exclusively for his landscape photography, it produced incredibly sharp negatives,

perfect for making large contact prints.

|

|

|

Panoramic Exhibitions

Henry began exhibiting panoramic views taken with the 18x22" camera. Three

separate contact prints were spliced together so precisely that it was impossible

to detect the joint, even on close scrutiny. The final prints were 18"

wide and 5 ft long, the largest contact prints ever made, and were displayed

at the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876. In March 1885, Henry's stereo

views were displayed at the New Orleans Exposition and in September at the Milwaukee

Exposition. He was invited to photograph special events like the "Ice

Palace" at the Winter Carnival in Minneapolis and Chicago's panoramic

paintings of the Gettysburg Cyclorama of 1893.

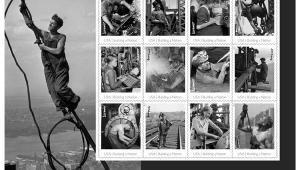

Stop-Action Shots

By now Henry was obsessed with the idea of stop-action photography and he began

experimenting with various designs, using springs and rubber bands. In 1886,

he tested his instant shutter-release device, which he affectionately called

the "snapper," and it worked. His stop-action midair photograph

of a lumber raft man throwing a rope from a raft, and another of son Ashley

leaping 5 1/2 ft across a 40-foot-deep chasm at Stand Rock, were probably the

first two stop-action shots ever made. Believing this impossible, some of his

peers thought he had manipulated these in his darkroom.

A new attraction also arrived at Henry's studio, a stereopticon, for projecting

black and white glass positives onto a screen. Like a magnet, it drew visitors

to his studio, eager to watch his "magic lantern" shows, which brought

the stunning landscapes of the Dells to life. Occasionally Henry used two lantern

projectors simultaneously to accomplish a dissolving effect very much like today's

slide shows, thrilling his audience. One slide, which never failed to amaze,

was Henry's son Ashley's leap across the chasm.

Henry was invited to give lantern shows in many cities including Chicago, New

York, and Boston. In February 1896, he presented a lantern slide show at the

Northwest Photographer's Association Convention in Minneapolis, which

received rave reviews. A highly impressed Oliver Wendell Holmes said, after

an outstanding performance in Milwaukee, that "...to sit in the darkness

and have these visions of strange cities, of stately edifices, of lovely scenery,

of noble statues, steal out upon the consciousness and melt away one with another,

is like dreaming a long beautiful dream with eyes wide-open."

Mass-Market Changes

Big changes in photography had already been set in motion with the appearance

of George Eastman's first Kodak camera in 1888. Mass-produced, these ultra-simple

box cameras with a fixed-focus 27mm f/9 lens came pre-loaded with a 100-exposure

roll of film for $25. Customers shipped the camera with exposed film back to

the Eastman plant where their pictures were printed, attractively mounted, and

returned loaded with a fresh roll of film. The cost was $10. The first photofinishing

service had been born and, like Eastman said, "You press the button. We

do the rest!" By 1900, the Kodak Brownie camera cost $1, came with a instruction

book, and was extremely affordable. Photography was now at a crossroads and

within the reach of many Americans, and the age of "snapshots" was

born. Tourists still came to the Dells, but now they brought their own cameras.

Henry's business slowed and ironically, son Ashley left the business and

joined the Eastman Kodak Company in 1894 as a traveling salesman.

After Henry died on January 1, 1908, his widow Evaline, along with his daughters,

continued to run the business, which was subsequently inherited by his children

and grandchildren. They made prints for sale using Henry's original negatives.

In 1976, recognized as the oldest family owned and operated photographic business

in the US, the Bennett Studio was placed on the National Register of Historic

Places. In 1978, Henry's revolving printing room, solar enlarger, along

with a few valuable glass plates were placed in the Smithsonian Institution.

Be Sure To Visit

Looking back 100 years, when busy Broadway was little more than a dirt road,

one can almost visualize Bennett, trudging back to his studio at dusk, exhausted

but exhilarated from a successful day's shoot.

Visitors can take home a special Bennett souvenir. A wide selection of affordably

priced, original handmade prints, made from second-generation negatives in the

darkroom attached to the museum are on sale. Each print is matted and mounted,

with H.H. Bennett's signature stamped in gold leaf, a tradition he started

more than a century ago, during photography's golden era.

The H.H. Bennett Studio & History Center is located in the heart of Wisconsin

Dells at 215 Broadway. It is owned and operated by the Wisconsin Historical

Society. For information on visiting hours and more, visit www.wisconsinhistory.org/hhbennett.

- Log in or register to post comments