The Digital Darkroom

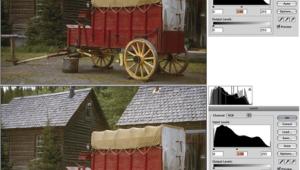

Working With The Desktop

| I've worked in a conventional,

wet darkroom almost all of my life. I can remember see-sawing black

and white film back and forth through open trays to develop it when

I was about 10 years old. I've been there and done that. |