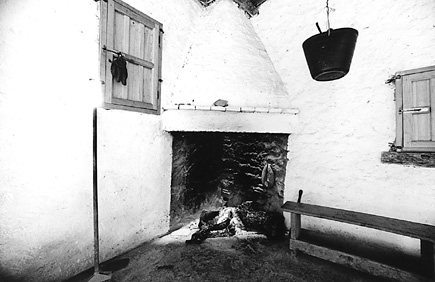

These are an amazing example of a good work on the black-and-whites. The pics look really fascinating and beautiful.

The Darkroom

Working With Imperfection Page 2

|

|

|

Dodging And Burning

The brightest white in a print is at most about 180 times as bright as the darkest

black: the brightness range is 180:1. A negative can easily record a brightness

range of 1000:1 and with reduced development it can handle 10,000:1 and beyond.

Some people mistakenly believe that you should be able to compress the subject

brightness range, no matter what it is, onto the paper. This takes no account

of how we scan a scene, with the iris of the eye constantly adjusting to different

light levels. It is much more natural, with most subjects, to dodge or hold

back the shadows locally, while burning in or darkening the highlights. A "difficult"

negative may need no more than localized dodging or burning to get an excellent

print, even at a normal grade. Remember, too, that with VC papers you can use

different grades in different parts of the print.

Pre-Flashing

If there is a lot of detail in the lightest tones of a picture, but you still

need plenty of detail in the other tones, a useful trick is often "pre-flashing."

This involves giving a very weak uniform exposure to the paper before printing

it, to overcome its "inertia": I use a second enlarger, with no

negative in the carrier, raised high on the column and well stopped down.

Determine the intensity of the uniform exposure by making a test strip across

a range that runs from no tone at all to the faintest of grays: typically 1-2-3-4-5

seconds at f/16. The last exposure that gives no tone at all, or the one before

it, is the one to use for a pre-flash.

|

|

|

Tonality

All right: you have a print with pure whites, good blacks, and a full range

of tones in between--and you still don't like it. What went wrong?

Here, we are in the most nebulous area of print quality: tonality. Good tonality

is easy to recognize, but hard to describe. To be brutal, bad tonality is even

easier to recognize.

The main reasons for bad tonality are poor exposure; poor development; and a

bad negative-paper match. This is an article about printing what you have, so

there is not much point in saying a great deal about the first two. On the other

hand, it is worth remembering that underexposure leads to far more problems

than overexposure, while at the development stage, overdevelopment is the most

common problem. It is also true that some developers suit some films much better

than others. If your chosen film-developer combination doesn't give you

tonality you like, try something else. Again, it's a question of knowing

when to quit. The aim of photography is to get good pictures, not to purify

the soul through suffering.

Back to the paper. If one paper won't give you the tonality you like,

try another: another make entirely, or another kind of paper from the same manufacturer.

Each paper has its own characteristic curve, its own way of rendering shadows,

mid tones, and highlights, and it can be astonishing how much difference this

can make. Some film-paper combinations "sing"; others may also sing,

but out of tune and flat. Even if you standardize on one paper, keep another--as

different as possible--for those negatives where you don't like the

tonality on your regular paper.

With less-than-perfect negatives, it is often a question of compromise, experimenting,

and perhaps settling for a print that is "good enough" rather than

absolutely right. But you may also find, in the course of your experiments,

that some of your prints from "hard-to-print" negatives are actually

better than you used to get from your "good" negatives. At the very

least, you'll be learning to print better, and to be more critical, and

that will stand you in better stead even with your most perfect negatives.

- Log in or register to post comments