The Art Of Photographic Recreation

How To Make An Image From The Minds Eye

Many times, when I have been

out driving, whether looking for pictures or not, I often catch a glimpse

of an image as I pass along the road. I'll stop, go back, get

out my camera and make some exposures. At other times, if without a

camera, I might catch a quick impression of a picture and that becomes

a remembered perception in my mind. Then, I'll go back later with

a camera to where I visualized the picture. Sometimes I'll make

exposures if I can capture that scene in a way that is reminiscent of

what I remembered seeing. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The French philosopher Roland

Barthes, in Camera Lucida: Reflections On Photography, discussed this

dilemma of photography. In that work he made one very revealing distinction

between photography and other creative visual arts. That difference expressed

by Barthes, put simply, is that photography is linked directly and permanently

to its subject, while all other creations of visual representation are

the result of a visual perception of the subject followed by the conscious

direction of the mind. This "direction of the mind" controls

how the artist's hand creates the picture. Although the camera is

indeed under the conscious control of the photographer, it, unlike drawing

and painting, records the subject by embedding reflected light directly

onto the physical media of the photographic process. This irrevocably

ties the image and subject together. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

At the time Barthes reflected

on photography, the process was still limited to physical media like film,

which captures the effects of focused light and records an image in silver

or dye, one that is forever bound to its supporting substrate. But once

an image could be either scanned or made directly with a digital camera

a photograph became information, data that could be re-arranged and manipulated

endlessly. When this occurred, the irrevocable bond tying a photograph

to its subject was broken. That freedom makes it possible to "rewrite"

a photograph to match any perception a photographer might have in the

mind's eye. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Tools For The

Journey |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Computer Applications

Used To Recreate Photographs |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

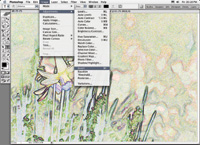

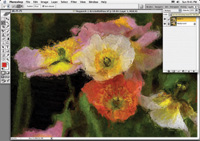

The next step in the process

is to produce a set of image effects variations of the 100dpi file. After

an effect is applied use Save As and add the name of the effect to the

file name and save the file in a "resource" folder. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Putting The Variations

Into Layers And Blending Finishing And Printing

Recreation Files

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Log in or register to post comments