Archiving For The Digital Studio

Protecting Your Images In The Digital Age

How important are your negatives

and transparencies? Do you have them neatly arranged in archival pages,

or strewn all over your living room floor? Even if you're not

a terribly organized person you realize the importance of the processed

film you've shot. While I've certainly lost film over the

years and had some precious negatives destroyed by water damage, by

and large I have carefully preserved almost all of my work. Stuff I

shot in the 1970s is still clean and ready to pull a new print, if I

need to. |

|||

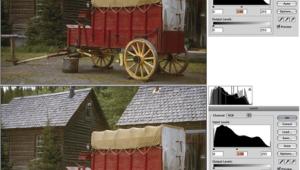

The Master Digital

File |

|||

Safe & Affordable

Storage |

|||

Make Sense Of It All Getting To Them On The Road Done Jobs |

- Log in or register to post comments