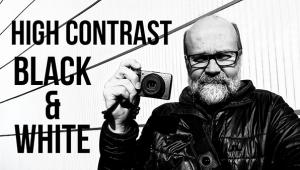

Seeing With A New Eye

Peter McDonough

| Peter McDonough is concerned

with perception; not the physiological aspects of perception, but rather

how the eye sees and converts its image, what people see and what they

don't see of a given subject. Quoting the Italian psychiatrist,

Roberto Assagioli, McDonough says, "`Eyes we have but we

see not.' On this I have based my photography." |

- Log in or register to post comments