The Last Windup: Steve McCurry Takes The Last Roll Of Kodachrome

Kodachrome was always a favorite of Steve McCurry, the internationally known photographer famous for his portrait of Sharbat Gula, the “Afghan girl,” taken for National Geographic magazine. When he heard the film would no longer be in production, he contacted Kodak and asked if he could take the last roll. “I don’t think there’s ever been, in the history of photography, a better film, a better way to actually look at the world than with Kodachrome,” McCurry said. “This was the only way I shot for decades.”

Audrey Jonckheer of the worldwide Film, Photofinishing and Entertainment Group at Kodak recalls that choosing McCurry to shoot the last roll was an easy decision. “Not only is Steve one of the world’s most revered photographers, but his passion for and ability to create some of the most iconic images on Kodachrome is unparalleled. What he captured for National Geographic in 1984 is arguably the most iconic image ever taken. So we thought it was only fitting for him to do the final honors with the last roll of Kodachrome.”

Kodachrome had been known for its sharpness, archival durability, and vibrant but realistic hues. Produced in a variety of formats, including 35mm slide film and 8mm movie film, its colors remain intact for decades. “I recently found a box of slides in my attic that had been there since the 1960s,” McCurry relates. “Despite the heat and cold, the colors reflected exactly what I had photographed.”

Kodachrome was invented in the early 1930s by professional musicians Leopold Godowsky Jr. and Leopold Mannes. Kodachrome employed a subtractive method as opposed to earlier additive screenplate methods such as Autochrome and Dufaycolor. Unlike other color films, it is black and white when exposed. It required a three-step development process to mix the primary colors, rather than having them built into its thin emulsion layers.

The film was used to record such momentous events as the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, Sir Edmund Hillary’s ascent of Mount Everest, and even Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm reel of President Kennedy’s assassination. Paul Simon said it best in his song Kodachrome, “You give us those nice bright colors, you give us the greens of summers…” And the Kodachrome Basin State Park in the red rock canyons of Utah has the distinction of being the only park named after a brand of film.

“Kodachrome has a wonderful color palette, and it was able to record the world as we actually see it,” McCurry says. “Without being garish or cartoonish like other films, it has almost a poetic look with beautiful colors that were vibrant and true to what you were shooting. It was the gold standard of imagery.”

The Last Roll

“What better way to honor the memory of Kodachrome than to try and photograph iconic people and places?” McCurry thought as he planned his journey. He spent nine months mapping out an odyssey that took him throughout India as well as his hometown of New York City, ending up at Dwayne’s Photo to hand-deliver the last roll. A film crew from the National Geographic channel followed him on his travels, and the special is due to air in the US in the near future.

Using his Nikon F6, McCurry chose to photograph the Rabari nomadic shepherds in Rajasthan, India, as he had recently worked with them and felt a personal connection. “They have a noble way of life; noble but vanishing. With roads, fences, and cities now in the way, many have resorted to working as day laborers. I’d be photographing them with Kodachrome, the best film ever made and also on its way out.”

All Photos © Steve McCurry

He then continued on to Mumbai to use Kodachrome’s magic to subtly render contrast and color harmony in depictions of Bollywood luminaries Shenaz Treasurywala (#1) and Amitabh Bachchan (#2). Back in New York City, every character line is noticed in Robert De Niro’s face, shown here in his Tribeca screening room to represent the American film industry (#3). “I look for the unguarded moment, the essential soul peeking out, experience etched on a person’s face. I try to convey what it is like to be that person, a person caught in a broader landscape that you could call the human condition.”

While Kodachrome is not generally thought of as a film to use for portraits, the enhanced colors and extreme details in these faces prove it can be the perfect choice. Note how clearly we can see the bloodshot eyes and the different skin colorations in the photo of the Rabari magician (#4). The bright red turban contrasts vividly with his white tunic.

What other film could possibly capture the intricate shades of orange in the photo of the tribal elder who dyed his hair and beard (#5)? We can easily see the scars on either side of his nose and the variety of colors on his face. Not one feature is under- or overexposed, which would be very difficult to do with digital. This is McCurry’s favorite photo from the roll because “it’s a captured moment of a lost way of life.”

The red, purple and gold in the Rabari girl’s outfit complement the blue wall she is standing against (#6). Her gaze is reminiscent of the Afghan girl who originally helped make McCurry famous. In his book Portraits, he notes that faces such as these “speak a desire for human connection, a desire so strong that people who know they will never see me again open themselves up to the camera, all in the hope that at the other end someone else will be watching—someone who will laugh or suffer with them.”

“I don’t know who is making up the rules regarding what film is best for portraits,” McCurry says. “One should be completely free to photograph with whatever he or she gets pleasure from or thinks is right—whether it’s in black and white, through a pinhole or with an 8x10 view camera.”

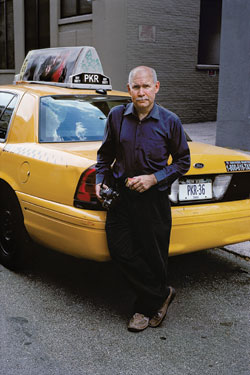

By a stroke of luck, McCurry found a Kodak-yellow taxicab with the license plate PKR 36 (the code name for Professional Kodachrome 36 film) and decided this would be the perfect spot for a self-portrait (#7). “Grant Steinle of Dwayne’s laughed when he saw it and said, ‘If I hadn’t seen it come off the processor myself, I would have sworn you had photoshopped it.’”

The Evolution To Digital

“We have gained so much for obvious reasons with the arrival of digital photography, but nothing can compare with the excitement of opening a box of processed Kodachrome and seeing all the beautiful color photos,” McCurry believes. “Digital certainly has a lot more capability and the picture quality is wonderful. You’re able to view, edit, and monitor what you are doing as you go. You can evaluate the light, composition, and design instantly. You can also shoot in extremely low light with digital, plus you can stop movement unlike using practically any film. There are many other benefits to digital, but you have to put most of them in during postproduction. As Ansel Adams used to say, a negative is like a sheet of music. A good printer then reads the music and can make the picture great. The same concept applies in producing digital photos.”

McCurry took no chances shooting the last roll of Kodachrome. To make sure he had exactly the right moment for each photo, in focus and at the right exposure, he first used a digital camera. “I wanted that reinforcement, to be able to see it on a two-dimensional screen,” he recalls. “The other risk with this last roll was having the film x-rayed twice going through the airport, but luckily it survived intact.”

Into The War Zones

McCurry first obtained fame when he slipped into Afghanistan before the Russian invasion, disguised in native garb. When he emerged, he had rolls of film sewn into his clothes of images that would be published around the world to show the conflict there. Since then he has traveled to many war-torn areas. “It’s in my DNA to want to tell stories about where the action is, that shed light on the human condition. It’s important to document areas in transition and places in conflict, so the world will know what is going on in countries like Libya, Afghanistan, and Iraq. I focus on the human consequences of war, not only showing the effect on the landscape, but more importantly, on the human face.”

A high point of his career was finding Sharbat Gula, the previously unidentified Afghan girl who helped make him famous. “After 17 years, I knew immediately this was the girl, with those beautiful green eyes and the distinctive scar on her nose. Her skin is weathered, there are wrinkles now, but she is as striking as she was all that time ago.” McCurry has been described as feeling sad about her current living conditions, but in reality he sees the glass as half full. “She’s still alive and leading a fairly normal life. Compared to many in our culture, she has more leisure time and is surrounded by friends and family.”

In addition to his worldwide travels, McCurry also finds the time to run the ImagineAsia project where textbooks and medical supplies are shipped to underdeveloped countries. The group also sponsors students to come to the US to study. In addition, he conducts photography tours to “visually interesting places” such as those scheduled for Myanmar and India next year. Details of the trips can be found on his website, www.SteveMcCurry.com.

McCurry donated all 31 photographs (a few were duplicates) to the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film in Rochester, New York. They will also be featured on an international tour starting in 2012. Meanwhile, McCurry still keeps a few rolls of Kodachrome in his refrigerator, partly for nostalgia and mostly for hopes that Kodachrome may someday be revived. “Kodachrome represents the impermanence of life in that everything eventually ends. But we had a wonderful time and we all loved it.”