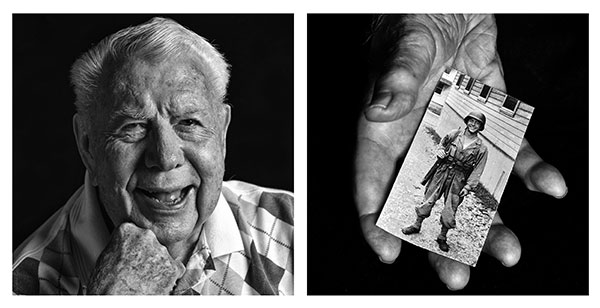

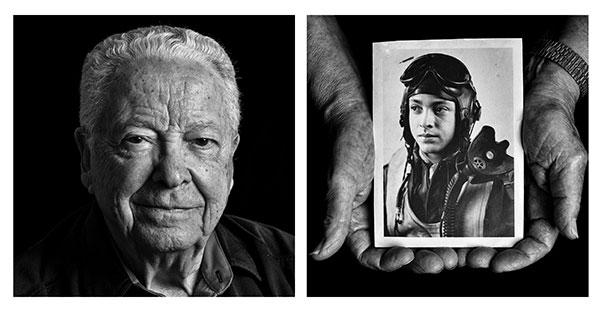

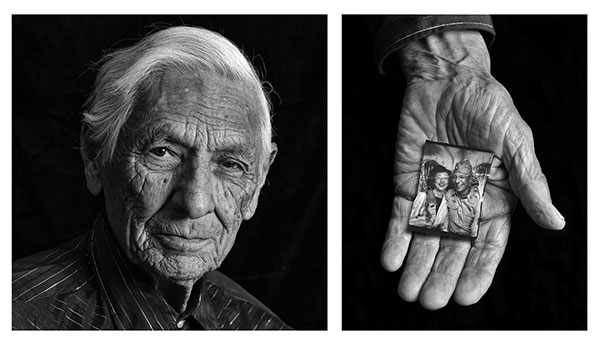

Face to Face: Richard Bell's Powerful Portraits Show World War II Veterans Now and Back Then

Richard Bell began photographing for his book, The Last Veterans of World War II, early in 2016 and completed the photography a little over a year later. But for the origin of the book, you have to go back to Bell’s childhood.

Growing up in the 1950s, he loved the picture magazines, like Life and The Saturday Evening Post, and he has a distinct memory of pictures of a Veterans Day parade in one of the magazines. “There were these incredibly old guys, with long white beards,” he says, “and the caption said they were our last Civil War veterans. To me, they might as well have marched out of the Roman Empire. I thought, They can’t be still alive, it’s impossible.”

That memory was the seed for The Last Veterans of World War II. “In 1996, with those Civil War veterans in mind, I started photographing World War I vets, but I ran out of time. I got six or seven—they all were 100-plus years old—and that was it, it was over. I said to myself, I won’t miss it next time.”

In 2016, with the youngest World War II veterans in their early 90s, he went to work. He photographed 44 veterans, creating not only portraits, but also accompanying images of the veterans holding pictures that link them to the past. “That’s the story,” Bell says. “The time between their hands today and the old photographs, and also the time between the old photographs and today’s portraits.”

Making the Connections

Finding the veterans wasn’t an issue. Bell’s concern was making sure his photographs represented their diversity and all the branches of the service. “It would have been easy to shoot 50 Battle of the Bulge veterans,” he says. “There are associations, and each has 20 guys or so, but I wanted variety.”

His first subject was a Marine who lived in his county. “There was a story in the local paper, and I ran the information down and took his picture. That was the start. From him came his buddy. Then I had to veer off the Marines, but [the project] kept moving. After I’d finish a portrait, I’d ask, ‘Is there anyone you can recommend who I can contact?’ And so many times I’d get a name, a phone number, even a ‘Do you want me to call him?’”

Other times, veterans’ associations helped him make contact. And always, the photographs opened doors. “I’d get a veteran on the phone, and I’d say, ‘Can I e-mail you a couple of pictures?’ and as soon as they saw them, they’d call back and say, ‘Yeah, I want that.’ The photography was the convincer; it worked almost every single time.”

Making the Portraits

In his career in photography—20 years in photojournalism followed by 20 years in commercial photography, and now “working on personal fine art and documentary projects”—his motto hasn’t changed: “Everything has to fit in carry-on.” And so for this project, there was no problem arriving at the veterans’ homes with a small kit that announced he was a “low key, low impact” sort of fellow.

He carried a Sony A7R II with a Sony FE 90mm f/2.8-22 Macro G lens, a Paul C. Buff AlienBees B400 160 Ws monolight, a lithium battery pack to power it, and a PocketWizard to remotely fire it into an umbrella. His portable background was a black velvet cloth.

“It has the quality of not reflecting light,” Bell says, “and it was perfect for me. I could just wad it up and put it back in the case; no need to fold it—you can’t see the creases.” He had no frame or support for it. “I always counted on someone in the family to hold it up for me when I made the portrait. And in a pinch, I carried gaffer’s tape to tape it up.”

He used the same setup each time, at the same distance from, and angle to, his subject. And he picked the right room in the house. “I needed some reflection because I had only one light, so I placed the subject in a room painted white and always tried to pick a chair where his dark side—away from the flash coming in at an angle—would be reasonably close to a wall so he’d get the spill from the flash. In the right room, with the right placement, one light can look like three.”

With Honor and Respect

In the book, Richard Bell writes, “I’m in the generation destined to honor and pay forward the achievements of our fathers, the veterans of World War II.” One measure of his respect for his subjects is that he imposed no time limit on his portrait sessions.

“Whatever the comfort level was for each veteran, that’s how much time I spent. The only limit was, I didn’t want them telling the history of World War II, so in some cases I’d stop them after a few minutes and say, ‘We’ve got this history down. What we don’t have is your story. What did you do?’ I got those stories by letting them talk for as long as they wanted to—some for 15 minutes, some for two hours.”

Many of the veterans tell their stories as if relating a job that had to be done; most barely acknowledge their own courage. Harlan Twible, a Navy ensign, tells Bell, “I read an article recently about me and it said I had saved 151 men. I didn’t save them, they saved themselves.”

The words and photographs in Richard Bell’s book are poignant reminders of how much is owed to these veterans for what they saved for us.

The website for The Last Veterans of World War II, published by Schiffer Publishing, is at thelastveterans.com. Richard Bell’s website, richardbellphoto.com, features images from the book.