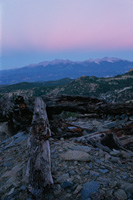

Earth's Shadow

Wait For The Right Light

In the Western US, sunrise

and sunset photography can often be especially challenging because there

aren't any clouds. Without clouds or haze, the sky simply fades

from a very pale, burnished blue to gray. No drama. No flash of color.

No spectacular light show. Nothing to add drama and interest to a photograph.

|

|||

Catching The Light Metering Options |

|||

Long Exposure Times Failure Of The Law

Of Reciprocity |

|||

Tech Data Guides |