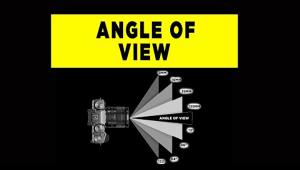

What Shape Is Your Picture?

Aspect Ratio Of Photographic Images

So, let's see--you

shoot with a 35mm camera and occasionally want the lab to make an 8x10

print for you. That's nice. Except whenever the lab does that,

they always cut off the edge of the picture. Or, they make a 7x10"

print and you are left with a lot of white space above and below your

picture. Either way, it isn't exactly what you wanted. |