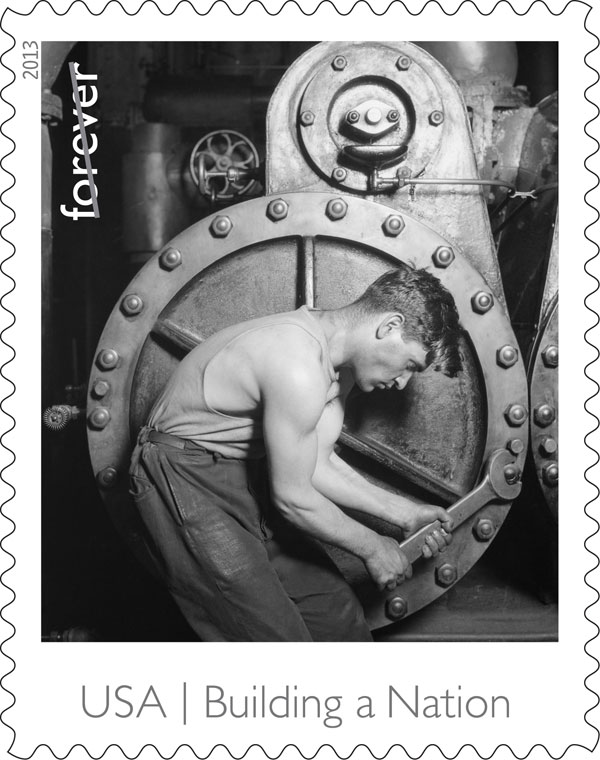

USPS Photography Stamp Release: Portrays “Made In America: Building A Nation”

The slight 56-year-old man who appeared at the Empire State Building construction site in New York on a spring day in 1930 probably failed to impress the workers he’d been hired to photograph. The 4x5 Graflex Lewis Wickes Hine carried seemed outsized in his hands. His thick, owlish glasses and demeanor contributed to the accurate impression that he was or had been a schoolteacher.

© 2013 USPS

But the diminutive photographer surprised the ironworkers—whom Hine christened the “Sky Boys”—by scaling the dizzying heights alongside them to capture what today stand as some of the most arresting documentary images made.

In order to obtain the best vantage points, Hine often was swung out in a specially designed basket 1000 feet above ground. Thus, he managed to capture, as no one had before, the dangerous—five men died during construction—and seemingly miraculous work of building skyscrapers.

Everything about the Empire State Building was as astonishing as Hine’s photos. From its completion in 1931 until construction of the World Trade Center’s North Tower in 1972, it stood as the world’s tallest building. Today, it still ranks as the 23rd tallest skyscraper in the world.

© 2013 USPS

At 102 floors and a height of 1250 feet, the building was constructed in just 410 days—completed three months early and greatly under budget because of reduced construction costs during the Depression. Before Hine’s camera, the ironworkers raised 57,000 tons of steel in just six months, almost 50 percent more than used in the Chrysler and Bank of Manhattan buildings combined.

But Hine almost didn’t take the job.

Until that time, he’d focused his camera primarily on the evils of child labor. After quitting his teaching job at the Ethical Culture School two decades earlier, Hine had applied photography to exposing the plight of child laborers. In tackling the Empire State Building assignment, he would prove to be as brave and resourceful as he did in documenting child labor abuses.

© 2013 USPS

The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC) hired Hine in 1908 to document the widespread and gross violations of existing labor laws, supposedly designed to protect children. During his years of photographing child labor in coal mines in Pennsylvania and cotton mills in South Carolina, he often posed as a Bible salesman or insurance agent to gain entry, then slipped away before he could be discovered and beaten up. The haunting portraits Hine brought back revitalized child labor laws and made him the preeminent practitioner of socially conscious photography of the period.

In 1938, aided by widespread publicity from Hine’s photographs, Congress passed the Fair Labor Standards Act that, in part, established more stringent child labor regulations.

But, during the Depression, Hine’s brand of sociological concern and photography were out of favor. He needed a job—even if it was working for the corporate America he had scourged in his child labor images. The last years of his life were filled with professional struggles resulting from the loss of government and corporate patronage. Few people were interested in his work, past or present, and Hine lost his house and went on welfare. He died penniless in 1940 at age 66.

© 2013 USPS

The New Issue

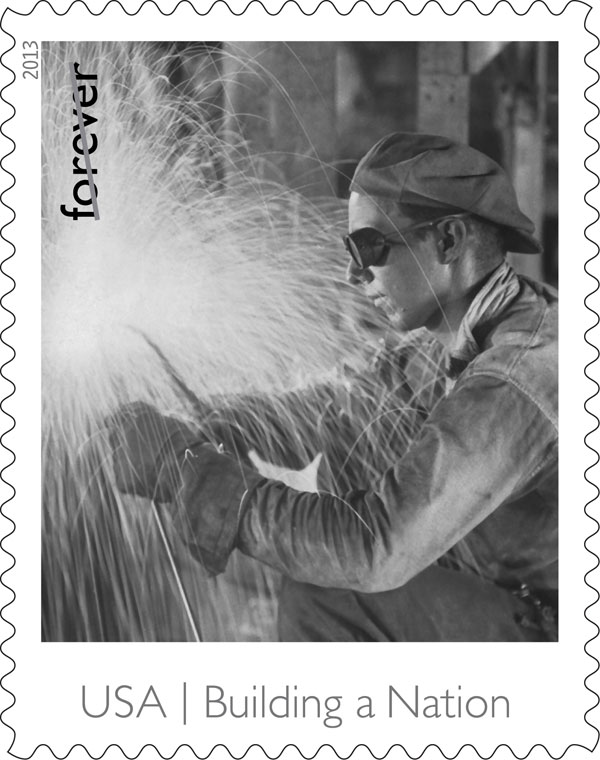

The 12-stamp “Made in America: Building a Nation” sheet released recently by the United States Postal Service (USPS), while presenting 10 of Hine’s images, is focused more broadly.

“We receive thousands of letters each year with stamp requests, including ones from coal, steel and other industries. The stamp sheet is an ideal way to honor a variety of industries and represent the men and women who helped build our country through their hard work,” according to a USPS spokesperson.

About the stamps, USPS Art Director Derry Noyes said, “In selecting images, I chose to highlight the dignity of hard labor that ordinary American citizens did day in and day out. The images also contribute to the pride Americans have about how we built our nation. Lewis Hine documented this better than anyone. His are powerful and beautiful portraits.”

Four of the 10 Hine images are from the Empire State Building series—six came from his series of work portraits. The other two photographs on the sheet were done by Margaret Bourke-White (“The Welder”) and an unidentified photographer (“The Coal Miner”). The latter was acquired from the Kansas State Historical Society.

© 2013 USPS

Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971) was an American photojournalist and—like Hine—a social realist. She is best known as the first foreign photographer permitted to take pictures of Soviet industry, the first female war correspondent—the first permitted to work in combat zones—and the first female photographer for Life magazine, where her photograph—dedication of the Ford Peck Dam—appeared on its first cover in 1936.

Five versions of the sheet are available with the same photographs but different background images—three are by Hine, one by Bourke-White, and the other by the unknown photographer.

The Library of Congress has archived more than 5000 Hine photographs. Other collections include nearly 10,000 images held by the George Eastman House and 5000 of his NCLC child labor photographs are at the Albin O. Kuhn Library & Gallery, University of Maryland.

The names and biographies of most of the men who worked on the Empire State Building are lost now. The same is true of the identities of other workers portrayed in the stamps. In releasing the sheet, the USPS is requesting help from the public in identifying some of the subjects. Information may be provided to Sarah Ninivaggi via e-mail at: sarah.a.ninivaggi@usps.gov.