The Portraits Of Phil Pantano: His “American Worker” Series

The idea for Phil Pantano’s photographic series, “The American Worker,” walked into his office at a local steel mill in Lackawanna, New York, where Pantano holds a day job as a computer analyst. The man who came through the door was Jay “Elvis” Borzillieri, a fourth-generation steelworker whose father died in the mill. It doesn’t matter to the story what Elvis stopped in for that day, but when Pantano looked into his face a flash went off in his mind. “It was the look of a man who was glad the day was over. Weary, but proud. You didn’t need to see the dirty clothes to know he’d just put in a full day’s work,” Pantano remembered. “Without a word his face said it all.”

Others have photographed workers at similar job sites, notably Buffalo’s own Milton Rogovin who over the years shot many a blue-collar worker on the job site. “I knew I wanted viewers to focus on the workers without the distraction of backgrounds,” Pantano said, “I wanted them to see that feeling in his face.” He had Elvis come to his home in Tonawanda (a suburb of Buffalo) one day after his shift was over, complete with the sweat, grime, and stress of the workday still very visible. “Black and white was chosen over color,” he added, “because I wanted to capture a certain mood.”

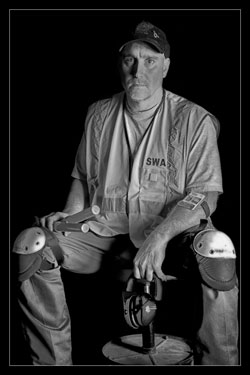

Kevin Downey - Kevin left the Buffalo area in 1994 after obtaining a two yr. degree. Settling in Las Vegas, he became a personal trainer until the company cut his hours in half. A client mentioned an airline was looking to hire and that started Kevin in his ramp agent career. Long hours, early mornings or late night shifts, sweltering sun in Las Vegas or snowstorms in Buffalo, and cramped bin locations too small for a six foot tall guy, are just part of the job. The knee and shoulder surgeries can’t stop the airline worker…it’s all part of this physically demanding job. He simply works through it. At the end of his shift, it is time to pick up his four children from school. He often has to make several trips back and forth to their catholic school so they can participate in activities. He has been dedicated to his airline for nearly 20 yrs., his wife for 25 yrs., and his children for 15 and counting. Kevin can often be found coaching his son’s baseball teams, watching his daughters’ softball games and dance competitions, as well as on the Judo mats himself.

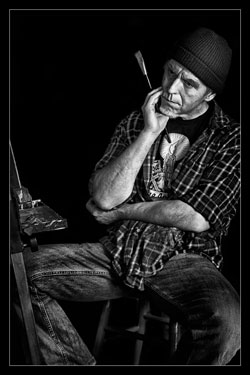

All Photos Photos © Phil Pantano/Photography by GreatLook

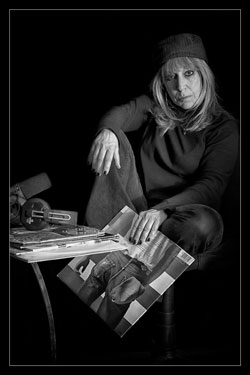

Sean Madden - Sean’s insanely surreal art has been published and exhibited all over the world. Sean grew up in Buffalo, then moved to Rochester in the 80’s. He has a masters degree in Counselor Education, and has been making and selling art for many years—everything from children’s books to oil paintings to dark surrealism. To date, he’s been published in the UK, Australia, Canada, Puerto Rico and throughout the US.

Anita West (97 Rock & WBFO) - Anita graduated with a degree in Radio/TV/Theatre from Ashland University. She began her radio career in Atlantic City, New Jersey before moving to Powerhouse Station WAAF - Boston, Massachusetts in 1986. Anita then went on to WHJY in Providence, Rhode Island. Moving to Western New York here in 1988 to work 10-3 on the newly revived 97 Rock, she currently hosts her own show on Saturday afternoons 2-6 on 97 Rock. An avid supporter of local music, Anita can be found every Thursday hosting Thursday Night Blues at Central Park Grill in Buffalo, NY.

Roberta Lew-Pokrzyk - Roberta is an Electrician in a large manufacturing facility in Buffalo, New York. She has been an Electrician for over 16 years. Her choice of employment field came out of necessity. Divorced and trying to make a decent life for her son, Roberta remembered something her father had always instilled in her: “Go back to school and learn a skilled trade and you’ll always have something to fall back on.”

The Series Is Born

It was after looking at the finished images of that session that another flash went off. He got to thinking about that carrot which is dangled in front of many workers—“The American Dream”—and how hard so many work to achieve it. Pantano started thinking about other people he knew who might be suitable subjects for a series of photographs. Of course, this being the age of the Internet meant he could bring up a whole list of people on his computer—some who he knew personally, and some who were just a face and an occasional comment on Facebook.

Two weeks later, “The Musician,” refined blues rocker Myron Sharvan, was his next subject. Sharvan’s music career started in 1972, so he, too, has “been around.” After that, the ball started rolling pretty fast.

Although Pantano never mentioned it, the subjects and titles of his images sound like something out of the old Donovan song “Atlantis.” Besides “The Steelworker” and “The Musician” there was “The Model,” “The Firefighter,” “The Priest,” “The Utility Worker,” and so on.

As the series grew it became apparent that not everyone was a worker in the mill, but all “shared in the myth of The American Dream,” Pantano said. “And it’s not only being chased by mill workers.”

It might be easy to say that a doctor, or even a priest, shouldn’t have any trouble chasing The American Dream. And you’d be partially correct only in the fact that maybe financially their struggles aren’t as severe as say a factory worker or a waitress who maybe is working two or three jobs to make ends meet. But Pantano points out that the 19 subjects in “The American Worker” series experienced the same kind of feeling at the end of their day—be it an eight-hour shift, a weekend spent on call, three hours on stage, or an overtime shift spent at a raging house fire—they were beat. Some mentally, some physically, some both. Beat, but satisfied.

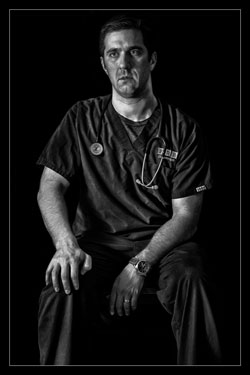

Mike Mineo - In Mike’s own words: “My journey to becoming an emergency physician included four years of college, followed by four years of medical school, and lastly three years of eighty hour work weeks during residency training. The financial cost is in excess of $150,000 in student loans despite scholarships and part-time jobs. The ongoing cost is long hours, working over-nights, and weekends and holidays away from my family. Birthdays are often missed and my children have become accustomed to attending parties without their dad. It is an immense privilege to treat patients at their most desperate times, but it is not without sacrifice.”

Michael Dorsey - Michael has been a Fireman for the city of Niagara Falls, New York, for over 4 years. He is also a part time Paramedic.

Denise M Abbott - Denise has been a nurse for over 10 years. She has been an Emergency Room nurse at DeGraff Memorial Hospital in North Tonawanda, New York.

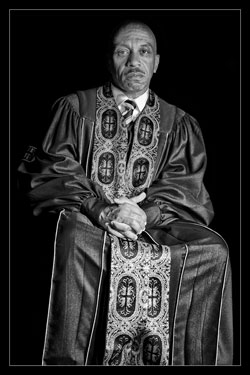

Rev. Darius G. Pridgen - Darius is a native of Buffalo, New York growing up in the Perry Projects and the East Side. Rev. Pridgen was an only child that grew up from very humble beginnings and has worked tirelessly his entire life. While the majority of the public knows him as Pastor Pridgen or Council Member Pridgen, he is affectionately known in his neighborhood as “Darius” or “Rev.”

The Exhibit

When Pantano’s photographic exhibit of all 19 subjects, 12 of which are shown in these pages, opened locally this past June at the Main (ST)UDIOS in downtown Buffalo, it got rave reviews from a packed house which came from all walks of life. And it wasn’t just 19 photographs hanging on a wall. The subjects were there in person, proudly hanging around to tell their stories; there were QR codes that linked to statistics on the American working public; and biographies of the 19 workers accompanied each photo. Some of them, such as “The DJ” and “The Pastor,” were already widely known to many of the exhibit-goers. In September, the show headed east on the New York State Thruway, where it spent three weeks at the Grass Roots Gallery in Rochester.

Tech Notes

The exhibit shots were taken with a Canon EOS 5D Mark II, using a tripod and exposures of up to five seconds. A black umbrella helped keep the lighting just where Pantano wanted it—on the faces. That lighting was accomplished using fluorescent CowboyStudio lights, with each subject seated in front of a black cloth backdrop. Some of the photos were taken in the subjects’ homes or garages—“This non-use of a professional studio only added to the grittiness of the shoot,” Pantano remarked, “as did the simplicity of the shots.” A black umbrella that any one of the subjects could very well have used on the way to the shoot; the inexpensive lights; even the “take a breath and hold it…hold it…hold it” method of bracing the subject for the longer exposure was old school and very much in character with the finished product.

The photos—shot in color—were then brought into Nik software: Color Efex Pro 4 to enhance detail, and Silver Efex Pro 2 to convert them to black and white and bring out even more detail in the faces. The files were then professionally printed in 20x30 format and mounted on foam.

Before the exhibit opened, when asked what he wanted to accomplish with the series, Pantano thought for a minute and replied, “I wanted people to walk away and think about what they’d seen. If they don’t know these people when they go into the show, they’ll certainly feel like they know them on their way out.”

Jay “Elvis” Borzillieri - Jay is a fourth generation steelworker with old world Italian values. His Father, Grandfather and Great-Grandfather worked in the steel industry. Jay is an assistant roller currently in his 16th year working for an Ohio based steel manufacturing firm. In his everyday duties, Jay is responsible for the proper operation of a red-hot rolling steel bar mill. Jay is also a rabid Elvis Presley fan.

Rachael Liptak - Rachael is a waitress working for 3 different restaurants. She has a 2 year old daughter. Rachael is also an aspiring model.

Jeffrey Barnes is an award winning photographer from Buffalo New York. He is the owner of Jeffrey T. Barnes Photography where he specializes in wedding, sports and portrait photography. Jeffrey has been photographing weddings since 1992 and is Chief sports photographer for Sports & Leisure Magazine and Metro Source Newspaper. In 2010 he won photographer of the year for creative excellence in the field of professional photography and in 2011, as a member of The Professional Photographers of America, Jeffrey earned the degree of Master of Photography.

Myron Sharvan - Myron, based out of Western New York, has a refined blues rock style. His music career started in 1972, working with many great musicians throughout the years. His current focus is new blues rock recording projects, gathering the finest musicians from all over the country to create traditional as well as contemporary sounds under his World Coyote Project banner.

You can see more of Phil Pantano’s work at www.greatlook.com, where you’ll also find contact and social media information.