Railroads plays a big part in our life. It takes us to the places that we ought to be. - Reputation Management

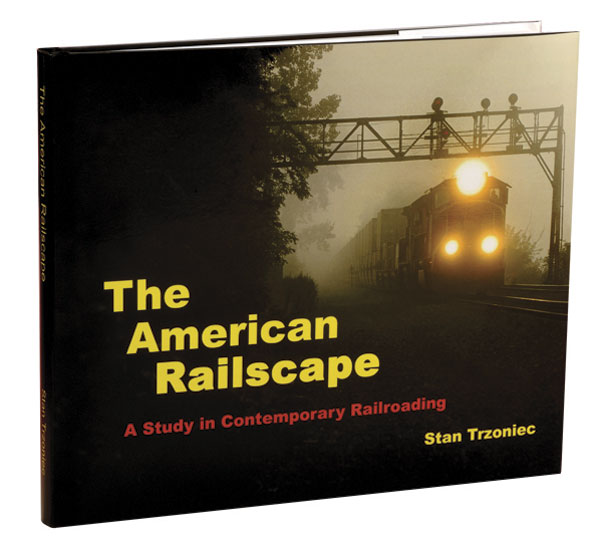

Personal Project: Photographing America’s Railroads: Shutterbug Contributor Stan Trzoniec’s Passion Turns Into A New Book

All Photos © Stan Trzoniec

I’ve been photographing trains for as long as I can remember. What exactly is the draw to photograph the railroad scene? If you think just shooting trains is at the top of the list, you are partially right. But it’s also the spirit of discovery. As you move around, you will see different locations, from the mountains in the east to the deserts in the west. Move in closer and you will notice the details on the older buildings, the abandoned lines and the efforts to conserve them.

You don’t have to be a “railfan” to appreciate the trains, as it doesn’t take long to see all the photographic possibilities. The main thing to remember is to stay off the right of way (tracks, ballast, and roadbed). Keeping 30 to 40 feet off either side of the tracks is a good policy, and never, I mean never, walk on the ties (in gauge) between the rails. Even though trains will make one heck of a racket going upgrade, coming downhill with welded rail, they can sneak up on you very fast. For the most part, and where a train might go into a rock cut, I use longer telephoto lenses, stay back from the tracks, and position myself at curves to get those neat profile pictures of trains bending around the curve. Out in the country—the Berkshires are a good example—you’ll be fine with a moderate zoom, which is perfect in combining both the railroad and some fine scenery.

And yes, like all photography, good train photography has a lot to do with observing light. Like many subjects, early morning and late afternoon give the best results. Soft light is good all day (cloud cover); front lighting is perfect for engines and, if your position is good, it will carry along to the length of the train. Sidelighting accents an almost three-dimensional effect and backlighting is great for steam engines working hard upgrade on a tourist line.

Since the prime movers are rather nondescript in appearance (after all an engine is an engine), camera angle along with the right location will make the most of your efforts. While you will probably start shooting from eye level, don’t be afraid to shoot from an overpass, hillside, or below track level. While head-on shots get full priority, don’t be afraid to tackle some photographs of a special passenger train moving away from you in the falling snow.

If you intend to sell some of your images, take into account the history of the line, perhaps include a famous landmark, station, trestle, or large horseshoe curve for interest. Keeping the photograph clean is important, as railroads during their maintenance cycles will discard old ties, tracks, tie plates, and utility poles along their right of way, so watch for these eyesores in your viewfinder.

Use shallow depth of field to perhaps zero in on an old station sign or a milepost with the waiting train in the background. Visit older stations and set up your camera in a far inside corner with a 20-24mm lens to capture the ambience of the building before it disappears. The use of a super-telephoto lens can isolate subject matter to your advantage, giving a completely new dimension to the railroad scene.

In my book, I have a chapter on Details Make the Difference and the Abandoned Landscape. With the former, I deal with the finer points of the railroad scene: useless “Armstrong” switch rods along the tracks, steam engines at rest, mileposts, discarded engines ready for the scrap yard, tired shop scenes. With the latter, which are my favorite, old buildings, diesels cannibalized for parts, vintage railroad cars in storage, a whistle post lying on the ground and surely forgotten are all part of the story. In short, if you run out of mainline action, delve into the sidelines. You’ll never be disappointed for the lack of photographic material.

A short time back I gave a talk at a local camera club about fleshing out the railroad scene as part of a monthly project by the club. They were all so interested in the idea that to this day it is still part of the club’s yearly assignments. Three weeks after I pen this article, it’s off to California to photograph the famous Tehachapi Loop (trains loop over themselves to gain elevation) and the Cajon Pass (spectacular mountain scenery) where the famous Santa Fe “Super Chief” made its mark.

I told you, it’s catching—the book has been 50 years in the making! See you trackside.

Stan Trzoniec is a frequent contributor to Shutterbug. His latest coffee-table book, The American Railscape is a study in contemporary railroading, available and autographed through his www.outdoorphotographics.com website for $125 plus postage. He can be reached via e-mail at fotoclass@aol.com. The American Railscape has nearly 300 photographs depicting railroads across the country. These photographs, picked from over 10,000 slides and digital images, are just the beginning of a line of self-published railroad books now in production.

- Log in or register to post comments