Choosing and Using Lenses

|

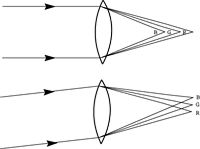

A great tool for creative photographers

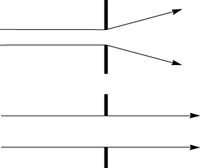

You can't beat the 35mm SLR for its combination of features, price and performance. And one its best features is its ability to accept a wide range of interchangeable lenses. From superwide fisheye to supertelephoto, macro close-up to soft-focus, fixed-focal-length or zoom, the perfect lens to suit any shooting situation is available for most 35mm SLR camera models. Canon offers lenses from 14mm superwide-angle to 1200mm supertelephoto for its EOS AF SLRs, Minolta offers focal lengths from 16mm full-frame fisheye and 20mm superwide-angle to 600mm supertelephoto for its Maxxums, Nikon offers autofocus lenses from 14mm superwide to 600mm for its AF SLRs (which can also accept a wide range of manual-focus Nikkor lenses), Pentax provides AF lenses from 17-28mm fisheye zoom to 600mm supertele for its AF SLRs (which can also accept manual-focus Pentax lenses from 15mm superwide to 1200mm supertele, and most can accept the 2000mm mirror), Sigma offers focal lengths from 8mm circular fisheye to 800mm supertele for its AF SLRs (and other brands of cameras), and so on. Why so many lens choices? Because there are lots of shooting situations. While many not-so-serious shooters can get by with a point-and-shoot camera and its built-in 35-80mm (or thereabouts) zoom, serious shooters use a wide range of lenses to handle a wide range of subjects. Action and wildlife shooters like long lenses that fill the frame with their subjects. Close-up buffs use macro lenses that let them move very close to their subjects. Landscape photographers use wide-angle lenses to capture grand scenic vistas (and other focal lengths for different effects). Portrait photographers prefer short telephotos, for pleasing head shots. This special section of the magazine will introduce you to the different types of lenses available, and show you how they can help in your photography. But first, here's a little general information on lenses. What Is a Photographic Lens? The following pages will teach you some things you should know about lenses and their use. And this knowledge will not only help you make better photographs, but it will help you select the lenses that are best suited for the type(s) of photography you do. How a Lens Works The focal length of a lens is the distance behind the lens at which images of distant subjects are focused: the distance between the optical center of the lens and the film when the lens is focused at infinity. Focal length is important because it determines the magnification of the image and the angle of view—how much of the scene will appear in the photograph. When a lens is focused on distant subjects, closer subjects will not be sharply focused. In order to focus on closer subjects, the lens-to-film distance must be extended. You do this by rotating the lens' focusing ring (or, with autofocus cameras, by partially depressing the shutter button to activate the AF system). When a lens is focused at a certain distance, theoretically a point at that distance will be reproduced as a point on the film. In real life, though, the subject point will appear as a small circle on the film. Points nearer or farther from the lens than the focused distance will appear as larger circles. These circles are called "circles of confusion." As long as they remain under a certain size, these circles appear to our eyes as points. That's what accounts for depth of field (more on this later). Bending of light rays (refraction) occurs because their velocity changes when they pass from one medium to another. Because short (blue) rays travel most slowly through glass, short rays are bent the most when they pass from air through a glass element. Long (red) rays travel most rapidly through glass and are therefore bent the least. Since light rays of different colors are refracted to different degrees, a single lens element can't focus all colors of light at the same plane. If it focuses green wavelengths at one plane, it will focus longer red ones slightly behind them and shorter blue ones slightly in front of them. The fancy term for this is chromatic aberration. By combining elements of different composition (high-dispersion and low-dispersion glass or other material), lens makers can reduce the effects of chromatic aberration and produce lenses that bring two of the three primary colors into focus at the same plane (achromatic lenses), or all three (apochromatic lenses). By the way, chromatic aberration affects the sharpness of black-and-white photos as well as color photos, because our subjects are in color even if our film isn't. Another thing that a single curved lens element cannot do is focus parallel rays passing through its center and its edges at the same plane. Rays passing through the edges are bent more and thus focused slightly in front of rays passing through the center. This is called spherical aberration, and lens designers can correct it by combining multiple lens elements. You can reduce it by stopping the lens down—spherical aberration is most evident at wide apertures. Another single-element lens problem is coma, which causes the small circles of confusion to appear elongated rather than round at the edges of the image. Still another single-element lens problem is astigmatism, the inability of the lens to focus horizontal and vertical lines at the same plane. Again, multiple elements help reduce the problem, as does stopping the lens down. |